What is Stalinism

In Russia at the beginning of the 21st century, much is said about the personality of Joseph Stalin and about Stalinism – an ideology that some worship, while others curse. However, very few people can define Stalinism and outline its main principles. In this article, we will attempt to examine this ideology, and we will see that Stalinism reflects the interests of certain social groups.

What is stalinism? Communist sources that do not criticize Joseph Stalin’s personality often argue that stalinism as such does not exist, that it is a “fiction”1, and what is meant by stalinism is merely a correct continuation of Marxism. However, if we refer to unbiased sources, we will notice that stalinism as a separate phenomenon does, in fact, exist. The New Philosophical Dictionary defines stalinism as “orthodox and official Soviet Marxism” of the 1930s-1980s, which was usually referred to as “Marxism-Leninism”2. Merriam-Webster’s dictionary defines stalinism as the political, economic, and social policies and principles that derive from Joseph Stalin’s activities, particularly: the theory and practice of communism developed by Stalin based on Marxism-Leninism, marked by especially harsh authoritarianism, extensive use of terror, and often an emphasis on Russian nationalism3. According to one definition from the Big Explanatory Dictionary by Kuznetsov, stalinism is a political trend within the communist ideology, based on the principles of leadership, ideological control over all aspects of society, strengthening the repressive function of the state, and the rejection of private property4. The divergence from other models of Marxism was especially highlighted by Roy Medvedev, who wrote that “stalinism is the distortion brought by Stalin to the theory and practice of scientific socialism; it is a phenomenon deeply alien to both Marxism and Leninism”5. We will provide a general definition: stalinism is a political theory that represents a revision of Marxist theory based on the views expressed in the works and policies of Joseph Stalin. stalinism also proclaims the course towards building a social state, but differs from Marxist theory in the following principles:

- The possibility of building socialism in a single country. Classical Marxists do not consider what was built in the USSR to be socialism, but stalinists disagree with this and often advocate for the return of planned economy without fundamentally reforming it compared to the economy of the Stalin era USSR;

- Confidence in the withering away of the state through its strengthening. Unlike Marxists, who believe that the state can wither away only by weakening, stalinists share Joseph Stalin’s view and advocate for the strengthening of the state and power;

- Strengthening class struggle as socialism progresses. This phrase hides the “search for the enemy”, which manifests itself in internal politics as a struggle against dissent through repression and in external politics as nationalism and the pursuit of expansion.

Another addition to Marxism is a change in the value system. While Marxism is more aligned with progressive values, stalinism shifts towards a conservative system of values, with the shift becoming more pronounced the “further right” it moves.

“Right-wing” stalinists advocate for intensifying the search for enemies, even to the point of fighting against other nations – such as Jews – and actively using religion in ideological work. “Right-wing” stalinism’s ideological positions nearly fully align with Nazism. Its representatives do not advocate for the withering away of the state (only for its strengthening) and are not strict in their views on economic issues.

Extremely “left-wing” stalinists might oppose nationalism, religion, criticize certain aspects of Joseph Stalin’s policies, and acknowledge the failure of the planned economy in the form it existed in the USSR. That is, they are partially influenced by progressive values and ideas of social democracy. However, in general, stalinism adheres, to a greater or lesser extent, to the principles we have outlined here.

In general, stalinists approve of the cult of personality, reject the usefulness of most democratic institutions, and are uncompromising towards any other viewpoints. Thus, some “right-wing” stalinists do not recognize Joseph Stalin’s mistakes, and any criticism is declared a lie.

Contents

Whose Interests Does stalinism Represent?

The answer to the question of whose interests stalinism represents can be found in one of its key principles: the strengthening of the state. Since stalinism advocates for the fortification of state institutions and power, while rejecting the role of democratic institutions, it is a beneficial ideology for the nomenklatura – that is, the unelected high officials, security services, and the layers of society serving the elite bureaucracy. The stronger the state power (and the lesser the degree of democracy), the more advantageous it is, primarily for the authorities.

Other principles of stalinism also serve the interests of these groups. The thesis of strengthening class struggle, as we noted, turned into a fight against dissent and nationalism. The fight against dissent is precisely what the authorities need to crush criticism within the country. Nationalism is what the authorities need to suppress external criticism.

A simple example: if nationalism is not strong in a society, then a statement, for example, by an American politician claiming that life in Russia is poor and there is no proper healthcare, will find support among the people who are indeed living poorly and without adequate healthcare. This could lead to mass protests and benefit society, but not the government. However, if nationalism is strong in society, people will believe the authorities, who will present the situation in such a way that “the American politician slandered Russia, in America hundreds of people are also starving, and here things are not so bad.” The authorities need nationalism to make such primitive attempts to play on people’s pride.

Does it serve the interests of society?

In contrast, the propagandists of the nomenclature stubbornly write in their books and speak on television that Joseph Stalin represented the interests of the common people and that stalinism benefits the majority. But a person who is capable of critical thinking should carefully consider how the principles of stalinism would benefit them. If the state and its organs are strengthened, will this benefit workers or intellectuals? The increase in bureaucrats and their stronger control over public life will not make life better for them — more of their own money will go to support this bureaucratic army. If the persecution of dissent and confrontation with other countries begins, will this improve the lives of office workers, teachers, or doctors? It will not, because they could be arrested for a wrong word (for example, criticizing officials), or have words attributed to them and be treated however the authorities see fit (since with weak democratic institutions, the state controls the police and courts better), and other countries could impose severe economic sanctions.

How stalinism was formed

Stalinism began to take shape in the 1920s when Joseph Stalin wrote theoretical works. In 1924, in his work “On the Foundations of Leninism”, Stalin wrote that “the proletariat of the victorious country can and must build a socialist society6“, which marked the emergence of his famous theory on the possibility of building socialism in a single country (although hints of this can also be found in the works of Vladimir Lenin). The key question lies in what was meant by the phrase “socialist society.” Friedrich Engels, for example, wrote the following:

Forced elections under the supervision of state-appointed authorities instead of factory overseers — that’s socialism! But you will inevitably come to this if you believe the bourgeoisie in something it doesn’t believe itself, but only pretends to believe: that the state is socialism!7

The Erfurt Program of 1891, approved by Engels, stated:

The Social Democratic Party has nothing to do with the so-called state socialism, a system of state appropriation for fiscal purposes, which places the state in the position of the private entrepreneur and thereby unites the forces of economic exploitation and political oppression of the working class in one hand8.

This was precisely what was built (the fact that the nomenclature, according to Marxist logic, exploited workers, we prove in this article) in the USSR by November 25, 1936, when Stalin, in his report to the Extraordinary VIII Congress of Soviets, stated the following:

Our Soviet society has achieved what it has already accomplished, in essence, socialism, creating a socialist system, i.e., accomplishing what Marxists call the first, or lower, phase of communism. Therefore, we have already accomplished the first phase of communism, socialism, in essence9.

This report determined that the concept of socialism in Stalin’s system of views was self-sufficient and, according to Stalin’s theory, represented what was built in the USSR by the end of 1936. However, this position was fully solidified only by this time, and in his speech on “Industrialization and the Grain Problem” on July 9, 1928, at the Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), Stalin introduced another core thesis:

As we move forward, the resistance from capitalist elements will increase, class struggle will intensify, and Soviet power, whose strength will continue to grow, will pursue a policy of isolating these elements, a policy of undermining the enemies of the working class, and, finally, a policy of suppressing the resistance of exploiters10.

In fact, this thesis justified all the violent actions of the government during Stalin’s era (it should be noted that similar thoughts were also previously expressed by Vladimir Lenin). Finally, in his report “Results of the First Five-Year Plan” at the joint Plenary Session of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) on January 7, 1933, Stalin expanded on this thesis:

The destruction of classes is achieved not through the fading of class struggle, but through its intensification. The withering away of the state will not come through the weakening of state power, but through its maximum strengthening11.

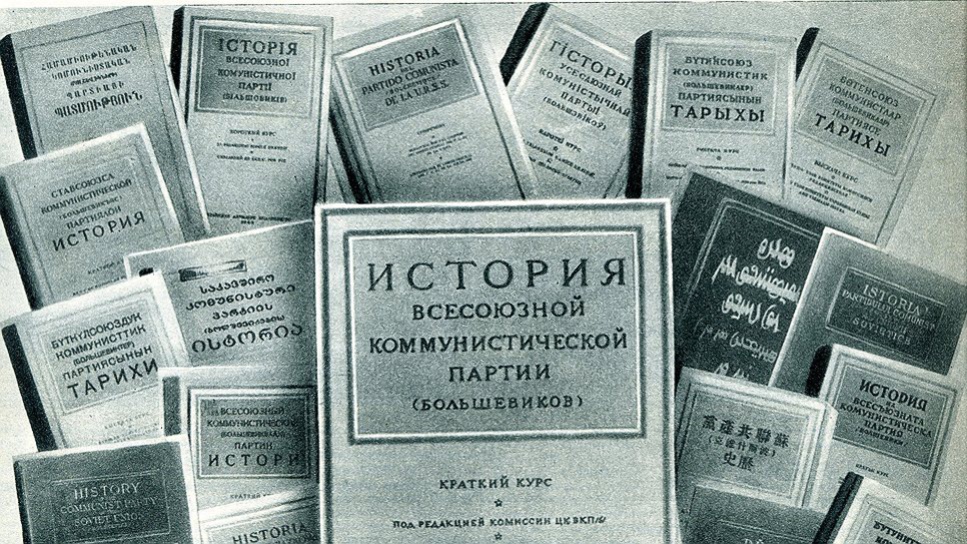

In 1938, the textbook “A Short Course in the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)” was published, outlining the views of stalinism on the history of the Bolshevik party (the falsifications in this textbook deserve a separate article, where it will be clear that Stalin essentially wrote the history of the party himself). It also became an important ideological document of stalinism, significantly influencing the historical views of this theory.

Development After the Death of Joseph Stalin

In his speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), Nikita Khrushchev effectively created his own version of stalinism, attempting to blend it with Vladimir Lenin’s theory and adapt it to the realities of the time (such as the defeat in the Kravchenko case). Ultimately, this version of stalinism did not include the personality cult, support for religion, or the thesis about the intensification of class struggle. However, other core elements remained: the acknowledgment of building socialism in the USSR, the necessity of a strong state, nationalism, and the fight against dissent (although less intense). The slogans of “unity of the proletarians of all countries” returned after Stalin’s slogans about the “Soviet homeland.” Khrushchev tried, in a softer form, to express the same ideas Stalin had; thus, at the 21st Congress of the CPSU, he effectively repeated one of the fundamental tenets of stalinism:

The question of the withering away of the state, if understood dialectically, is the question of the development of socialist statehood into communist self-government12.

In the same speech, he also confirmed that his concept of socialism aligned with Stalin’s, as he allowed himself to speak of the “world of socialism”:

The world of socialism is now stronger, united, and indestructible like never before. It exerts a decisive influence on the entire course of human development. It can be said with full confidence that the countries of socialism lead the entire progressive movement13.

Finally, Khrushchev directly gave a positive evaluation of Stalin (we remind you – at the 21st Congress):

Implementing the policy of industrializing the country and collectivizing agriculture, our people, under the leadership of the party and its Central Committee, headed by I.V. Stalin for many years, carried out profound transformations. Overcoming all difficulties in their way, breaking the resistance of class enemies and their agents – Trotskyists, right-wing opportunists, bourgeois nationalists, and others – our party and the entire Soviet people achieved historic victories and built a new, socialist society14.

Under Brezhnev, Khrushchev’s version of stalinism weakened, and the country returned to classical stalinism – elements of Stalin’s personality cult resurfaced, policies towards religion became more tolerant, proletarian slogans disappeared, replaced by nationalism.

In 1970, a bust of Stalin was installed near his grave by the Kremlin15 (and according to some sources, Leonid Brezhnev personally presented the monument and removed the covering16). Stalin’s image was also reflected fragmentarily in the historical and memorial complex “Mamaev Kurgan”, completed in 1967, where Stalin is depicted with soldiers celebrating victory. Stalin returned to historical films, novels, and books, often not in a negative light. The Presidium of the Central Committee was renamed to the Politburo, and the head of the party became known as the General Secretary (as Stalin had been), not the First Secretary (as Khrushchev was).

Scientists, writers, and artists noticed trends of rehabilitating Joseph Stalin, which were surfacing in speeches and publications, and in 1966, they wrote the famous “Letter of Twenty-Five” protesting the possible rehabilitation of the former General Secretary, which was later supported by the “Letter of Thirteen.” The nomenclature did not like the intellectuals’ response – at the 23rd Congress of the CPSU, Nikolai Yegorychev, the first secretary of the Moscow city committee of the CPSU, stated:

Recently, it has become fashionable to… search for elements of so-called “stalinism” in the political life of the country and scare the public, especially the intelligentsia, with it. We say to them: it won’t work, gentlemen!17

Besides Yegorychev, who was defending stalinism instead of condemning it, those advocating for a return to the more authoritarian stalinism included KGB officers Alexander Shelepin and Vladimir Semichastny. The latter tried to resume the fight against dissent by initiating the trial of Sinyavsky and Daniel, to which the intelligentsia responded with a “meeting of glasnost.” Candidate of historical sciences Sergey Semanov describes the events of that period:

The main event took place in 1969, on Stalin’s 90th anniversary. The year began with a sharp attack by Shelepin’s supporters: an article with a clearly pro-Stalin tone appeared in “Kommunist”, accusing liberal ideologues, with several Central Committee members and one of Brezhnev’s assistants, Golikov, among the signatories. The upper-level stalinists received support from their own faction: in the middle of the year, a combative novel by Kochetov, “What Do You Want?” appeared in “Oktyabr”, sharply critical of détente and rapprochement with the West. However, Kochetov had no fresh positive ideas, and he sharply and hostilely distanced himself from Russian revivalism (the novel was so scandalous that it wasn’t published as a separate book, but only in Minsk – Mashirov was a staunch opponent of détente and a fighter against Zionism, and he ultimately paid the price). By the end of the year, Stalin’s writings were being prepared for publication, but… nothing came of it, as Suslov’s people prevailed18.

The intelligentsia’s speeches gave Brezhnev the confidence to remove the right-wing stalinists from top positions when the convenient occasion arose – Svetlana Alliluyeva’s defection to the West, which was blamed on the security services19. Since the fall of Shelepin and his allies, the process of returning the nomenclature to the original stalinism came to a halt. Before Perestroika, the theory was not significantly changed.

The Renaissance of “Right” stalinism

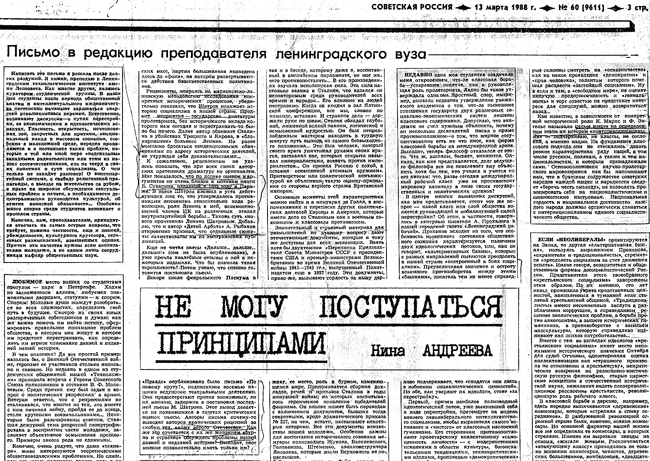

In 1988, during the rehabilitation of the victims of stalinist terror, an article by Nina Andreyeva, a previously little-known chemistry professor at Leningrad Technological Institute, titled “I Cannot Compromise on Principles” was published in the newspaper “Sovetskaya Rossiya”, defending classic stalinism. This article was probably the first to include the false “Churchill speech” praising Stalin, and immediately after this fabricated passage, Andreyeva hypocritically accused “left-liberal socialists” of falsifying history. This article can be considered the manifesto of the stalinists, marking the beginning of their resurgence.

At a Politburo meeting on March 24 of the same year, Mikhail Gorbachev realized that this was a collective manifesto:

The issue is not even the content of Andreyeva’s article or its mere appearance. There have been worse publications. But what stands out is the attitude towards this article, its evaluation as a standard, the recommendation to reprint and widely promote it… It is unlikely that Andreyeva wrote this article herself. How could she know what Fedoseev was discussing with Gorbachev, Ligachev with Yakovlev? …Who in Moscow instructed to study this article in the party education system?20<…>

Clearly, Andreyeva could not have written such an article on her own. Who inspired her? It is unclear. But there is the editor-in-chief of the newspaper, a candidate for membership in the Central Committee. This is not just a literary device. It’s a concept, the essence of which is that everything seemed fine before. So is Perestroika really necessary, and haven’t we gone too far with glasnost and democracy?21

At that meeting, stalinists made their presence known. Chief among them was Yegor Ligachev, CPSU Central Committee Secretary for Organizational-Party Work and Ideology, and the main initiator of the failed anti-alcohol campaign.

Ligachev. …The West has thrown the term “stalinism” at us. Through newspapers and magazines, the thesis about the necessity of other parties is circulating…22

After Gorbachev sharply rebuked him, no further approval of the article was voiced at the Politburo, making it difficult to determine the position of some other members. Alexander Yakovlev also recalled how, before the meeting, Gorbachev said, “I realized that this article had been made directive. It is already being discussed in party organizations as foundational. They have forbidden printing objections to it… This is a different matter”23.

Overall, the letter demonstrated that stalinists were present even in the highest circles of the USSR at that time and were influencing ideology, even before this point. For example, on July 12, 1984, at a Politburo meeting, many statements were made from the perspective of stalinism:

USTINOV. In my opinion, Malenkov and Kaganovich should have been reinstated in the party. They were, after all, prominent figures, leaders. I’ll say outright, if it weren’t for Khrushchev, the decision to expel these people from the party would not have been made. In fact, there wouldn’t have been those blatant atrocities that Khrushchev allowed in relation to Stalin. Stalin, no matter what they say, is our history. No enemy has caused as much harm as Khrushchev did with his policies towards the past of our party and state, as well as towards Stalin…

GROMYKO. He dealt an irreparable blow to the positive image of the Soviet Union in the eyes of the outside world.

USTINOV. It is no secret that the Westerners never liked us. But Khrushchev gave them such arguments, such material, that it discredited us for many years.

GROMYKO. In fact, this is what led to the birth of so-called “Eurocommunism.”

TIKHONOV. And what he did to our economy! I myself had the opportunity to work in the regional economic council.

GORBACHEV. And to the party—dividing it into industrial and agricultural party organizations!24

During Perestroika, stalinists, lacking decision-making authority due to the political system’s centralization (ironically, their own creation and program point), but possessing a strong composition, including in significant state positions, focused on ideological work. In 1988, one of the first publicistic panegyrics to Stalin was published with a 70,000-copy circulation25 – Vladimir Uspensky’s novel The Secret Advisor to the Leader (later published in large quantities – for example, in two books, each with a 500,000-copy circulation by the “Soviet Patriot” publishing house), and in 1989, the text Katastroika by Alexander Zinoviev, criticizing Perestroika from stalinist positions, was released. In 1990, the Letter of 74 was published, with classic Nazi-style accusations of the government’s course being “Russophobic”, “genocidal to the Russian people”, “sycophantic towards Judaism”, “rewriting history” without specific examples, searching for “Zionists in the Soviet press” and the Politburo. Among the signatories were “right-wing” stalinists such as Alexander Prokhanov, Vadim Kozhinov, and Mikhail Lobanov. And in 1991, Felix Chuyev’s book 140 Conversations with Molotov was published, from which many myths and legends originated.

In the same year, 1991, stalinists attempted a coup by declaring the State Emergency Committee (GKChP) as the ruling authority. The leaders of the GKChP were:

- Central Committee member Gennady Yanayev (in his book “GKChP Against Gorbachev” he wrote: “On Stalin and our Soviet past, a torrent of all kinds of slander poured out (of course, not for the first time)26”);

- Marshal and Minister of Defense Dmitry Yazov (in one interview he said: “People yearn for the former greatness of the country, for the victories achieved under Stalin, for the confidence with which the people looked into their future, for the justice that reigned in society at that time27”);

- Head of the KGB Vladimir Kryuchkov (wrote in the book “Personality and Power”: “The time when the country was led by I.V. Stalin was difficult, hard, and at the same time glorious28”);

- Central Committee member Vasily Starodubtsev (when asked “Would you have worked with Stalin?” replied: “Undoubtedly. And any person with a state mindset, who thinks about the fate of the country, would have worked with him29”);

The statements and actions of these individuals suggest that they were indeed stalinists, and most likely, so were the other committee members. The coup attempt failed, and all the leaders were arrested.

Revenge of stalinism

After the failure of the GKChP coup, the stalinists again resumed their ideological work, having accumulated a lot of experience from past mistakes. It seems that this time they decided to avoid involvement in “palace” intrigues, understanding that unsuccessful attempts push them backward. This time, they decided to first conquer the ideological field, displacing their rivals—market-oriented nomenklatura. In the late 1980s, the latter were more ruthless, hungrier, and more agile. But now they had grown old, and a new generation of similarly power-hungry stalinists was emerging.

The ideological field was now being seized not by the nomenklatura (including the generals), KGB workers, or propagandists, who had failed to reach the trough in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but rather by individuals like the ones already mentioned: Yazov, Yanayev, Kryuchkov, Starodubtsev, and others, including:

- Richard Kosolapov, author of the collection “Word to Comrade Stalin” – a former employee of the Central Committee of the CPSU and editor-in-chief of the “Communist” magazine. He was removed from his position as editor in 1986. In an interview with the newspaper “Zavtra”, he claimed that “Stalin outplayed everyone”30;

- Mikhail Alexandrov, author of the book “Stalin’s Foreign Policy Doctrine” – employee of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1982-1992); leading expert at the Military-Political Research Center of MGIMO31;

- Nikolai Velikanov, author of the book “Betrayal of the Marshals” – editor-in-chief of the Soviet Defense Ministry’s journal “Soviet Military Review” (1986-1989), former responsible editor of the central bodies of the Ministry of Defense32;

- Mikhail Dokuchaev, author of the stalinist book “History Remembers” – deputy head of the 9th Directorate of the KGB of the USSR from 1975, retired since 198933;

- Vladimir Zhukhray, author of the book “Stalin. Truth and Lies” – head of the analytical department of Stalin’s personal secret service34;

- Vladimir Karpov, author of the book “Generalissimo”, a notorious document falsifier35 – former GRU worker36;

- Alexander Prokhanov, author of the book “The Fifth Stalin” – editor-in-chief of “Soviet Literature” magazine from 1989 to 199037;

- Arsen Martirosyan, author of the book series “200 Myths about Stalin” – former KGB colonel38;

- Vladimir Uspensky – former worker of DOSAAF “Patriot of the Motherland”, who wrote his novel “The Secret Advisor to the Leader”, as he himself admitted in the preface, in collaboration with nomenklatura members and generals39;

- Sergey Kurginyan, television propagandist of stalinism – took part in nomenklatura privatization, and by special permission from the district executive committee, Kurginyan received at least two buildings for the “Experimental Creative Center”40;

- Vasily Soyma, author of the book “Forbidden Stalin” – retired FSB colonel, president of the Foundation for the Assistance of Veterans and FSB Employees of Russia41;

- And many others.

As we can see, the state security agencies consistently form the core of stalinists. They know that if everyone believes in the legitimacy of Stalin’s repressions, it will be easier to justify their own, opening up great prospects for enrichment. With the arrival of Vladimir Putin to power, the budgets and capabilities of the FSB in ideological work seem to have expanded, and stalinist historians are multiplying like mushrooms after the rain. How do they appear? Part of the answer to this question was given by historian Nikolai Yakovlev, who, in the appendix to the book “August 1, 1914”, detailed how ideological operations were carried out in the KGB and how, in the 1970s, he was recruited by Yuri Andropov42. On the directive of the KGB, he wrote the book “CIA vs USSR”, published in a circulation of over 3 million copies. By proving that the CIA and American diplomats in Moscow were directly involved in editing and rewriting the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who, according to Yakovlev, was a “loyal servant of the CIA”, Yakovlev falsified a quote from the memoirs of the American ambassador to Moscow, Jacob Beam. Yakovlev also, in an attempt to discredit academician Andrei Sakharov, wrote slanders about the personal life of his wife, Elena Bonner. Sakharov then tried to file a lawsuit accusing Yakovlev of defamation, but the local court refused to accept his documents.

Stalinism also receives support from an unexpected side – from American sensationalist hunters such as Arch Getty or Grover Furr.

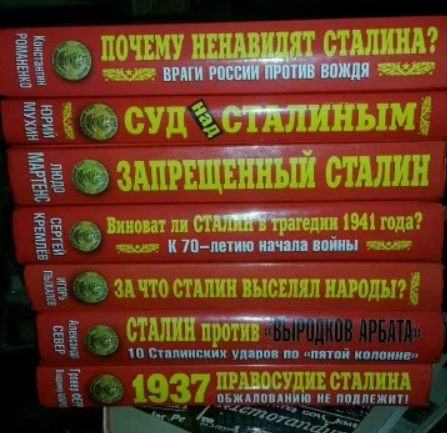

However, for the most part, the emergence of stalinist historians is not connected with recruitment and ideological operations (which were necessary at the initial stage), but rather with following market trends. After the Perestroika reforms and the 1990s, which cannot be fully described as successful, a demand arose among the masses for an opposition stance to the government by market-oriented nomenklatura members. stalinists, who had the greatest remaining resources from the Soviet era, hastened to fill this gap with their ideological works, thereby usurping a significant part of the anti-government agenda. The people began to believe that the best enemy for this government was Joseph Stalin, and that stalinists would shoot all the thieves. Consequently, there arose a demand for stalinist literature, and various publicists took it upon themselves to meet this market demand.

This includes well-known folk-history writer Alexander Bushkov, former Russian fantasy author Elena Prudnikova, Nazi Yuri Muhin, the one who apologized to the Ingush for the lies, Igor Pykhalov, plagiarist of Arch Getty’s ideas Yuri Zhukov, commercial director of Putin’s First Channel 43, Nikolai Starikov, and numerous other forgers such as Vladimir Kucherenko (Maxim Kalashnikov), Andrei Fursov, Mikhail Delyagin, Yuri Emelyanov, Dmitry Lyskov, Sigismund Mironin, Alexander Kolpakidi, Konstantin Romanenko, Alexander Sever, Alexander Shabalov, and others. Stalinists assert that the authorities are trying to slander Stalin and hide the truth about him, but if that’s the case, then why are the above-mentioned printed in tens, sometimes hundreds of thousands of copies, with some even appointed to the First Channel (the myth of the “slandered Stalin” we discussed separately)?

Further Plans of the stalinists

Can we speak of a stalinist conspiracy, with all of them acting collectively and in sync? Of course not. The nomenklatura simply follows its own interests, expressing stalinist views. We can only speculate that one of the major centers conducting “ideological operations” is somewhere within the state security agencies. Everything else tends to develop more spontaneously. However, these individuals do act relatively harmoniously, and even their different factions, as if conspiring, repeat the absurdities from the stalinist legendarium. But this is not the result of a conspiracy; it’s the result of personal interest or insufficient awareness.

Most likely, they will continue to increase their presence in the information space, while improving the quality of the lies. For instance, if Yuri Muhin simply engaged in blatant falsification, Yuri Zhukov now skillfully hides his false conclusions among a large number of real facts and objective reasoning.

If they manage to succeed in today’s Russia, it will likely be accompanied by the following measures:

- A revision of official history, introducing a “new version” with an infallible Stalin, inflaming interethnic hostility and falsifications;

- The establishment of total ideological control;

- Strengthening the FSB and granting its employees exceptional powers, allowing them to “close” practically anyone;

- Extensive political repression against liberals, Trotskyists, anarchists, social democrats, and some of their own allies who deviate from the government line;

- Repression against ethnic minorities and sexual minorities;

- Repressions against some members of the current nomenklatura as well, but only to take their places or “get a hand on it.”

If you have the illusion that stalinists will introduce the institutions of a welfare state, you can see from their works and books that they are little interested in these topics, do not study them, and if they write about them, it is briefly, in the style of “we need to do this for everyone to be well” or “we need to return everything as it was, and it was good then.” They are interested in justifying repressions, fighting Jews, the “greatness of the state”, fighting the “rewriting of history” (though they are primarily the ones rewriting it), fighting liberals and Trotskyists, and glorifying the image of Joseph Stalin. Here they are ready to write entire books, and this reveals their true motives.

In a country like Russia, building a social state with an efficient economy, which would be competitive on the world market on one hand, and based on fair distribution principles on the other, could only be done by progressive social democrats or some democratic left-wing forces, but not stalinists or the current nomenklatura in power.

- On stalinism // Politshstorm (politsturm.com). July 1, 2017. [Electronic Resource]. URL: https://politsturm.com/k-voprosu-o-stalinizme/ (Accessed: 02.03.2021).

- New Philosophical Dictionary / Compiled by A.A. Gritsanov. – 896 pages. – Minsk: Published by V.M. Skakun, 1998.

- stalinism // Dictionary by Merriam-Webster: America’s most-trusted online dictionary (www.merriam-webster.com). [Electronic Resource]. URL: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stalinism (Accessed: 02.03.2021).

- Big Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language / Compiled and edited by S.A. Kuznetsov. – 1536 pages. – St. Petersburg: “Norint”, 2000. – p. 1259.

- Roy Medvedev. To the Judgment of History. On Stalin and stalinism. – Moscow, 2011.

- I.V. Stalin – On the Foundations of Leninism

- K. Marx and F. Engels. Works. Second edition. Volume 35. – 525 pages. – Moscow: Political Literature Publishing House, 1964. – p. 140.

- K. Marx and F. Engels. Works. Second edition. Volume 22. – 805 pages. – Moscow: State Political Literature Publishing House, 1962. – p. 623.

- I. V. Stalin – Report to the Extraordinary VIII Congress of Soviets

- I. V. Stalin. On Industrialization and the Grain Problem – July 9, 1928, at the Plenary Session of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

- I. V. Stalin. Report “Results of the First Five-Year Plan” at the joint Plenary Session of the Central Committee and the Central Control Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) on January 7, 1933

- Materials of the Extraordinary 21st Congress of the CPSU. – 259 pp. – Moscow: State Publishing House for Political Literature, 1959. – p. 93.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- R.G. Pikhoya. The Soviet Union: History of Power. 1945-1991. Second revised and supplemented edition. – 684 pp. – Novosibirsk: Siberian Chronograph, 2000. – pp. 322-323.

- “Stalin’s Personal Guard.” The Main Directorate of the NKVD – P. Deryabin

- XXII Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. March 29 – April 8, 1966. Stenographic Report. In 2 volumes. Vol. 1. – 640 pp. – Moscow: Politizdat, 1966. – p. 126.

- S.N. Semanov. Dear Leonid Ilyich. – 368 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, Eksmo, 2006. – pp. 227-228.

- A.V. Filippov. Modern History of Russia, 1945–2006: A Book for Teachers – 494 pp. – Moscow: Prosveshchenie, 2007. – p. 188.

- In the Politburo of the CPSU… Based on the records of Anatoly Chernyaev, Vadim Medvedev, and Georgy Shakhnazarov (1985–1991) // Compiled by A. Chernyaev (project leader), A. Weber, V. Medvedev. 2nd edition, corrected and supplemented. – 800 pp. – Moscow: Gorbachev Foundation, 2008. – p. 299.

- Ibid., p. 304.

- Ibid., p. 300.

- Ibid., p. 305.

- R.G. Pikhoya. The Soviet Union: History of Power. 1945-1991. 2nd revised and supplemented edition. – 684 pp. – Novosibirsk: Siberian Chronograph, 2000. – pp. 388-389.

- T.V. Morozova. Sailor, Writer, Citizen. — Moscow: Shcherbinskaya Printing House, 2007. — 79 pp.

- G.I. Yanayev. GKChP Against Gorbachev. The Last Battle for the USSR. – 240 pages. – Moscow: Eksmo, 2010. – p. 146.

- “Father of the Nations”: Marshal Yazov on the monstrous lies and truth about Stalin // Newsland (newsland.com). September 20, 2016, 09:38. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://newsland.com/community/1460/content/otets-narodov-marshal-iazov/5450018 (accessed: 12/07/2019).

- Personality and Power. Vladimir Kryuchkov. Enlightenment, 2004 – Total pages: 381

- Would you have worked with Stalin? // “Kommersant Vlast” magazine No. 18, May 10, 2010, p. 8. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/1366354 (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Author’s blog “Zavtra” editorial. In his time, Stalin outplayed everyone… (Well-known Marxist philosopher answers questions from “Zavtra” correspondent) // Zavtra Newspaper (zavtra.ru). January 14, 2003, 00:00. [Electronic resource]. URL: http://zavtra.ru/blogs/2002-01-1471 (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Mikhail Alexandrov – author IA REGNUM // IA REGNUM (regnum.ru). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://regnum.ru/analytics/author/mihail_aleksandrov.html (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Velikanov N.T. // Young Guard (gvardiya.ru). [Electronic resource]. URL: http://gvardiya.ru/publishing/authors/velikanov_nt (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Hero of the Soviet Union Mikhail Stepanovich Dokuchaev // Heroes of the Country (www.warheroes.ru). [Electronic resource]. URL: http://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=1279 (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Ekaterina Sazhneva. Steel Mask. Published in the newspaper “Moskovsky Komsomolets” No. 24765, May 20, 2008 // Moskovsky Komsomolets (www.mk.ru). May 20, 2008, 16:22. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.mk.ru/editions/daily/article/2008/05/20/40023-stalnaya-maska.html (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- A. Dyukov. “The Soviet Story”: Mechanism of Lies. – 88 pages. – Moscow: REGNUM, 2008. – pp. 14-17.

- Nadezhda Zhiltsova. We Need a Common Goal. “Teacher’s Newspaper”, No. 27, July 6, 2004 // Teacher’s Newspaper (www.ug.ru). [Electronic resource]. URL: http://www.ug.ru/archive/4640 (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Biography of Alexander Prokhanov // РИА Новости (ria.ru). February 26, 2018, 02:01. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://ria.ru/20180226/1515074349.html (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Roman Ukolov. FSBwagen. What stands behind the scandalous road race of FSB Academy graduates // Lenta.ru (lenta.ru). July 4, 2016, 00:05. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://lenta.ru/articles/2016/07/04/fsbwagen/ (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Uspensky V.D. The Secret Advisor to the Leader. Novel. Book 1, Moscow — Prometey, 1989, p. 5-6

- Kurginyan – Aleksashenko “Nomenklatura Privatization” // YouTube (www.youtube.com). December 25, 2011. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZGj1yCCR-o (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Vladimir Komissarov. The Foundation for the Assistance of Veterans and FSB Employees of Russia // Chekist.ru (www.chekist.ru). [Electronic resource]. URL: http://www.chekist.ru/article/1635 (accessed: 27/11/2019).

- Yakovlev N. N. On “August 1, 1914”, historical science, Y. V. Andropov, and others // August 1, 1914. — Moscow: Moskvitianin, 1993. ISBN 5-86553-001-4

- Contact Information. // First Channel St. Petersburg (www.1tvspb.ru). [Electronic resource]. URL: http://www.1tvspb.ru/pages/contacts/ (accessed: 27/11/2019).