What is the nomenklatura

Progressive social democrats cannot fail to understand that as long as the division of labor persists, society will continue to be divided into classes. The class that takes on the management of production will, in this case, become the dominant one, effectively the 'elite' of society. In the Soviet Union, this class turned out to be the nomenklatura, which, overall, proved to be worse than entrepreneurs. We will examine this in a series of articles about it.

In our view, the failure to acknowledge the shortcomings of the USSR or to justify them is a far more serious obstacle for the left than even open opposition to the leftist movement, because, as is well known, “one’s own fool is worse than the enemy”. The incompetence, greed, and thirst for unlimited power of the Soviet nomenklatura is a fact that is easily proven (including in this article), and any attempts to justify it can evoke nothing but bewilderment in an educated person. This is not something to justify; it is something to fight. So, let us first honestly, without attempts at justification, examine the phenomenon of the Soviet bureaucratic layer.

Contents

- What is the nomenklatura

- How the concept was discovered

- The USSR nomenklatura from a marxist perspective

- How the Dictatorship of the Nomenklatura is Carried Out

- Were the nomenklatura socialists?

- Morals of the nomenklatura

- Secrecy

- Plus or minus?

- Purely a soviet phenomenon?

- How to prevent the formation of a new nomenklatura

What is the nomenklatura

In the “Concise Political Dictionary” (editions of 1964, 1968, and 1971), “nomenklatura” is defined as a list of positions for which appointments are approved by higher authorities1. In the textbook for party schools “Party Building”, the nomenklatura was defined as follows:

Nomenklatura is a list of the most important positions, the candidates for which are preliminarily considered, recommended, and approved by the relevant party committee (district committee, city committee, regional committee, etc.). Individuals included in the party committee’s nomenklatura are also released from work only with its consent. The nomenklatura includes employees occupying key posts2.

Here is the opinion expressed about the nomenklatura by Academician Andrei Sakharov:

Although relevant sociological research in the country is either not conducted or classified, it can be stated that already in the 1920s–1930s, and definitively in the post-war years, a distinct party-bureaucratic layer had formed and stood out in our country — the “nomenklatura”, as they themselves call it, the “new class”, as named by Djilas3.

However, with the fall of the USSR, the nomenklatura was by no means destroyed. Members of the Soviet government who led the country to economic catastrophe and collapse were not only not removed from power. These individuals, if they did not retire, either became part of the new government or became owners of large enterprises. Many of the privileges of the nomenklatura, established even under Stalin, remain to this day. Russia is still governed by the nomenklatura, as we can see from this article, so we need to provide a more modern definition based on the main research on this topic — the book “Nomenklatura” by Doctor of Historical Sciences Mikhail Voslensky.

Nomenklatura is a social class consisting of individuals holding the most important state and administrative positions, who have obtained these positions through non-democratic means, and who control the political and economic system of a given state. In other words, the term nomenklatura refers not only to the Soviet elite but also to the state elite of any other authoritarian country.

In full accordance with Lenin’s definition of a class, it is a large group of people distinguished from other groups by its — dominant — place in the historically determined system of social production, thereby in relation to the means of production, by its — organizing — role in the social organization of labor, and, consequently, by the manner of obtaining and the amount of that — excessive — share of social wealth at its disposal4.

According to Voslensky’s calculations, the approximate number of the nomenklatura in the late USSR was about 3 million people5.

How the concept was discovered

In 1957, the book “The New Class” by Milovan Djilas was published. Djilas, a member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia since 1932, had undergone underground work, imprisonment in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and participation in the partisan anti-fascist movement, later becoming a member of the Politburo of the Yugoslav Communist Party and one of Tito’s deputies. In it, Djilas wrote that the communists, having seized power and carried out the nationalization of the means of production (thus gaining the ability to control them), had become a new class of exploiters.

Speculations about the formation of a new class in the USSR had been made earlier. In 1936, the Moscow correspondent for the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine, Porzgen, wrote that in the USSR there had been a “new class formation, the development of the now ruling privileged layer”6. The Yugoslav communist Ante Ciliga, after several years of work in the USSR and subsequent exile, wrote in his book published in Paris in 1938 that in the Soviet Union “an entirely new class rules — the bureaucracy of communists and specialists”7.

In 1970, Mikhail Voslensky’s work “Nomenklatura” was circulated in the USSR via samizdat (this article largely presents its concise summary), which established most of the concept of the nomenklatura.

The USSR nomenklatura from a marxist perspective

From a Marxist perspective, that is, the theoretical framework upon which the USSR was built, the nomenklatura is an exploiting class. The first proof of this is the pronounced economic inequality in the USSR, described in the article on the privileges of the nomenklatura.

The second proof is the existence of a strong state, which according to Marxist theory itself “is a special organization of force, an organization of violence for the suppression of a class”8.

The state is a product and a manifestation of the irreconcilability of class contradictions. …the existence of the state proves that class contradictions are irreconcilable9.

Since the bourgeoisie and nobility did not exist in the USSR, which class was the state suppressing? And between which classes was the contradiction, if not between the nomenklatura and others?

The third proof is the control over the means of production. The privatization of state property in the 1990s was organized by the State Committee of the Russian Federation for the Management of State Property, meaning that the nomenklatura, not the enterprise workers, controlled the assets. During World War II, decisions regarding the evacuation of institutions and enterprise equipment (which is essentially equivalent to control over the means of production) were made by the Evacuation Council under the USSR Council of People’s Commissars10, that is, the nomenklatura. When producing the GAZ M-20 “Pobeda”, the pre-production models were demonstrated on June 19, 1945, in Moscow to the highest state and party leadership headed by Joseph Stalin11, which chose the version for mass production. The nomenklatura, just like capitalists, also decided whom to promote — for example, the chairmen of collective farms were appointed by the bureaus of district party committees12. These are just a few examples.

The fourth proof is that the nomenklatura carried out exploitation and appropriation of surplus value. How exactly this was done is discussed in this article. Therefore, if you have encountered Marxist apologists who repeat the Soviet propaganda thesis that “there was no exploitation in the USSR because there were no private factory owners”, you will see that they are using demagoguery.

Sometimes, nomenklatura propagandists claim that many regional party secretaries and factory directors in the USSR started as workers, and therefore power in the Soviet Union was in the hands of workers. However, if many billionaires in the United States started as shoeshiners, that does not mean that power in the U.S. was in the hands of shoeshiners. Class membership is determined not by origin but by one’s role in social production and the distribution of capital in the current period.

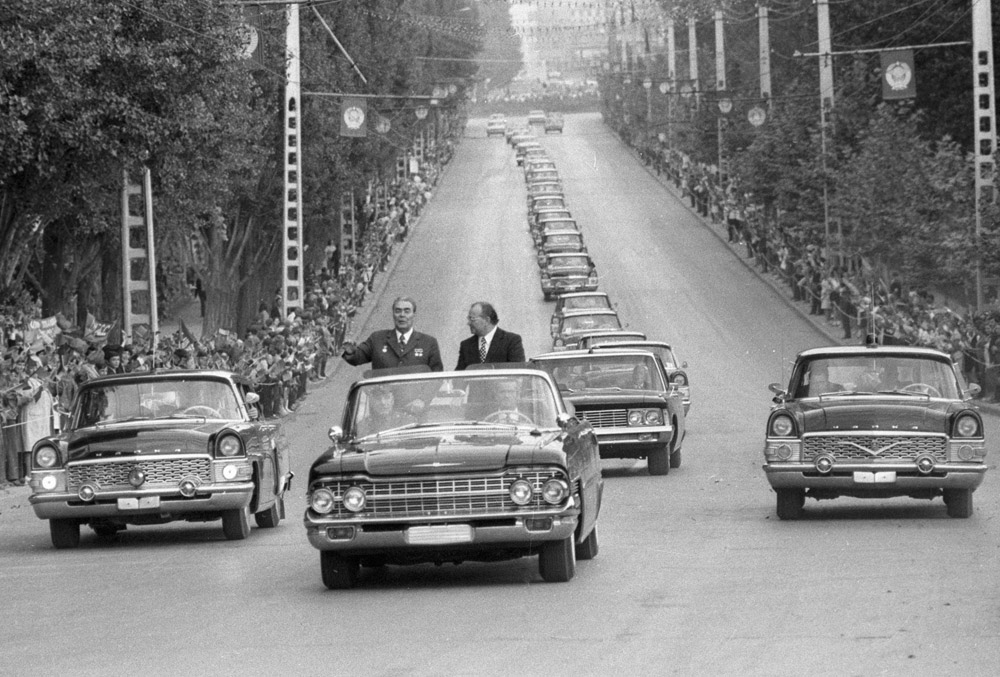

How the Dictatorship of the Nomenklatura is Carried Out

The nomenklatura maintained democratic institutions only as a facade; in reality, they decided nothing. Mikhail Voslensky described who actually made decisions in the USSR:

The centers of decision-making for the nomenklatura class are not the Soviets, so generously enumerated in the USSR Constitution, but the bodies not mentioned in it. These are the party committees at various levels: from the Central Committee to the district party committee. They, and only they, made every single political decision of any scale in the USSR. The official government bodies were merely lifeless moons, shining with reflected light from these stars in the nomenklatura class system.

The supreme bodies of the CPSU party committees (as well as other communist parties) are — in full accordance with the party charter — the plenums of these committees, that is, meetings of all their members.

But in fact, it is not the plenums that decide the issues. Decisions are made by the bureaus (in the CPSU Central Committee — the Politburo) and the secretariats of the party committees. This is where the final decisions are made. Only a few of them are submitted to the plenums, and then only as a formality13.

The process of developing and making decisions is described by Voslensky in detail14; we will not reproduce it fully here, only noting that it required a very extensive bureaucratic apparatus.

By the late 1920s, all more-or-less ideologically committed leftists had been pushed out of the highest leadership of the country and were eliminated in the second half of the 1930s because criticism of Stalin’s theories — such as “the withering away of the state through its strengthening”, the “intensification of class struggle on the way to socialism”, or other revisions of Marxism — was equated with Trotskyism, and therefore with “counter-revolutionary Trotskyist activity”, which in most cases led to the death penalty. We discussed the mass extermination of communists in detail here.

After the late 1930s, people joined the party primarily to advance their careers. Up until 1985, new members memorized the 1961 program, which stated that “in the next decade (1961–1970), the Soviet Union, creating the material and technical basis of communism, will surpass the most powerful and wealthy capitalist country — the USA — in per capita production”. This program also promised that by 1970, the transition to a six-hour workday would be completed, and by 1980 every family, including newlyweds, would have a comfortable apartment15. Even at the stage of memorizing these promises, any trust in the party and in socialism was lost, because these promises were not fulfilled even remotely, and the party leadership did not care about the program — it had not even read it and did not consider it necessary to update it until 1985, when it suddenly remembered its existence.

Pavel Sudoplatov, Lieutenant General of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, recounted:

In the following years, my wife and Aitingon, as it turned out, were far more realistic in their assessment of our system than I was. I remember, Leonid often said, for example, that the party was no longer a band of like-minded individuals devoted to socialist ideas and principles of justice, but had become merely a machine for running the country. At first, his jokes about the country’s leadership upset me, but later I got used to them and came to understand how right he was, believing that our leaders placed their own selfish interests above the interests of the people16.

The communists themselves built such a system — the absence of democratic institutions allowed the most cunning bureaucrats and careerists, rather than ideologically committed people, to rise to the top.

Morals of the nomenklatura

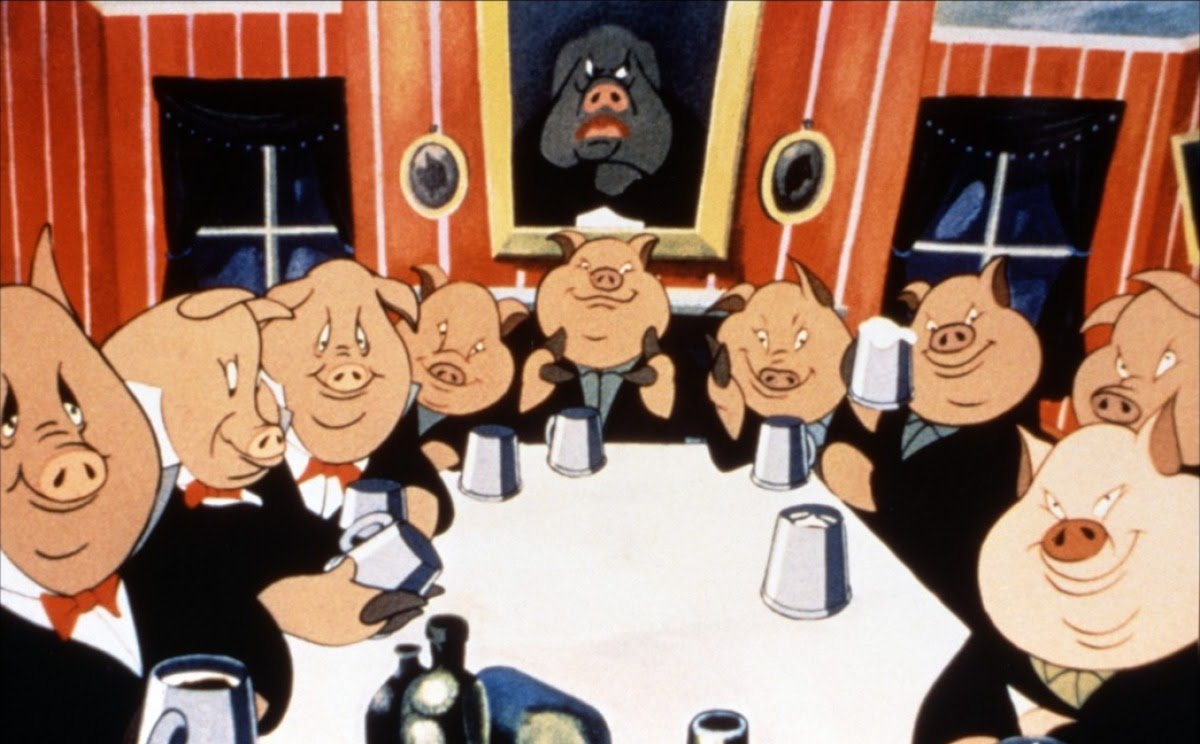

While verbally professing love for the people and concern for their welfare, in everyday life the nomenklatura not only hated the people and considered them uneducated rabble, but also sought to minimize contact with the “commoners”. Mikhail Voslensky described the relocation of the CPSU Central Committee canteen to a special building as a result of the nomenklatura’s desire to isolate itself from the people they “love”:

Although the walk from the Central Committee to 25th October Street is not far — just 10 minutes on foot — and generally pleasant, the insufficient separation of the canteen from the surrounding world caused dissatisfaction among the nomenklatura. They found it burdensome to walk among the usual Soviet crowds filling the streets around Dzerzhinsky Square during the day. As always, the displeasure of the nomenklatura was wrapped in the form of political vigilance. Rumors began that, suddenly, a foreign agent might stand near the canteen, photograph those entering — and, voilà, the portraits of the entire CPSU Central Committee apparatus would end up in a CIA dossier.

As expected, this argument immediately took effect. In the alley next to the Central Committee building, adjacent to a charmingly integrated 17th-century church, a three-story, bright canteen building was constructed. Entry was allowed only with CPSU Central Committee passes, which the KGB guard at the door carefully checked. People who were not employees of the Central Committee apparatus but performed some work in the building were also admitted with special passes. An hour before closing, staff of the Higher Party School and the Academy of Social Sciences under the CPSU Central Committee were also allowed in17.

We have already written about the “special stores”, “special sanatoriums”, “special schools”, and other separate institutions for the “white people” of the USSR in the previously mentioned article on privileges. Workers, collective farmers, the intelligentsia, and other social strata were regarded by the nomenklatura only as slaves who built communism specifically for them:

Under real socialism, it was indeed possible for a person to have a 100-square-meter apartment — and even a country dacha — for a negligible fee; to easily buy a car, or better yet, receive one as a gift along with a driver; to eat well and cheaply and feed the family, to use good clinics and hospitals for free, and to vacation every year in a sanatorium at no cost. All this was possible in the USSR. But to achieve it, one had to become a member of the nomenklatura class.

For the direct producers, the nomenklatura clearly defined the limits of their material possibilities: 12 square meters of living space per person; modest food; cheap transport to work and back; inexpensive newspapers and other propaganda literature, and for the intelligentsia — cheap permitted books so that in their free time they read instructive materials without thinking critically; medical care if sick, only enough to return to work quickly; a small old-age and disability pension (the limit for most — 120 rubles); a funeral allowance of 20 rubles18.

The nomenklatura considered themselves the new nobility and masters of life. During Perestroika, when more could be openly discussed, “Pravda” reported that in Dagestan, the first secretary of the Tabasaran District Committee of the CPSU, Osmanov, “went so far as to dislike being addressed by his first name and patronymic, demanding to be called ‘akhyur,’ which translates as ‘Your Majesty'”19. As Voslensky wrote, this did not prevent him from being promoted to first deputy minister of forestry of the Dagestan ASSR20.

Secrecy

Of course, the nomenklatura found it somewhat awkward, given its declared commitment to Marxist ideology, to enjoy its privileges. Therefore, it not only avoided contact with the people but also sought to keep both its existence and its special position in society as secret as possible:

The power of the feudal class was masked as divinely sanctioned rule of the king and those to whom he delegated it. The “New Class” takes this disguise even further: it conceals its very existence… the class of “managers” employs all its skill in mimicry to present itself as part of the normal — though under real socialism always pathologically inflated — state apparatus, an army of ordinary employees found in all countries of the world.

<…>

All data on nomenklatura positions are strictly confidential. Nomenklatura lists are considered top-secret documents. Only a very limited circle of people receive printed, book-style lists with replaceable pages titled “Lists of Leading Employees” — though, one might wonder, what could be secret about them?21

Plus or minus?

The rule of the Soviet-Russian nomenklatura had certain advantages, which it had to inherit from the Bolsheviks it had destroyed and from the period of their achievements. These advantages were mainly related to culture and social guarantees. However, over time, most of these benefits were dismantled, and the overwhelming majority of “innovations” that the nomenklatura introduced into the political system were rather negative. These include the system of privileges and Stalin’s “innovations”, which can also be equated with nomenklatura practices. When the nomenklatura attempted to implement democratization and economic reforms in the 1990s, they did so as incompetently and unfairly as they had handled everything else. A huge portion of the nation’s wealth went — and still goes — not only to maintain their properties and families but also to massive military, punitive, and ideological machines, as well as policies of expansion abroad. This resembles an organized criminal group that seized the country as a result of the Stalinist state coup and now “protects” it.

When the political and economic course changes, the nomenklatura will inevitably find a way to adapt it to its own benefit, which is why there is only one solution regarding them — nomenklatura lustration. After this process, truly professional, effective, and honest leaders will return to the administrative apparatus, those who committed economic crimes will be held accountable, and the inefficient will be removed from office. This is only the first, easiest part of the necessary work. A more difficult and responsible task lies ahead.

Purely a soviet phenomenon?

There is a stereotype that the term “nomenklatura” is used only in relation to the ruling class of the USSR or to the ruling class of countries led by a communist party. However, this is incorrect. The nomenklatura is the ruling class of all authoritarian states where mechanisms for openly transferring property and privileges by inheritance are underdeveloped. The most authoritative researcher on the nomenklatura, Mikhail Voslensky, also noted this:

Accordingly, the fascist and Nazi nomenklaturas did not kill the golden-egg-laying hen of the military-industrial complex: they did not seize enterprises from their owners, but were content with complete control over the economy22.

Thus, in Italy under Benito Mussolini and in Germany under Adolf Hitler, a nomenklatura also existed. However, this is characteristic not only of states under the control of communists or fascists but of any authoritarian power in general:

When, after Tito’s break with Stalin, Soviet propaganda declared communist Yugoslavia a fascist state, and the same happened with Pol Pot’s Cambodia, and Mao’s regime began to be semi-officially called fascist, people in the USSR could not fail to notice the ease with which the concepts “real socialism” and “fascism” were interchangeable… One can call the societies and political-bureaucratic dictatorships of the 20th century totalitarian, socialist, ordinary fascist — whatever. What matters is that all these societies form a single group, opposing modern parliamentary democratic society.

The main features of totalitarianism became clearly crystallized, allowing one to identify a totalitarian society without error. The primary feature is the emergence of a new ruling class in society — the nomenklatura, that is, a political bureaucracy with a monopoly on power in all spheres of social life. This class strives to keep secret not only its structure and privileges but also its very existence. An external sign of the emergence of the nomenklatura is the creation of a new-type party; the core of the nomenklatura appears in the form of the political apparatus of this party. Accordingly, a one-party system is established, in which there is either only one party or other formally existing parties are merely puppets of the ruling party’s apparatus23.

How to prevent the formation of a new nomenklatura

Since the nomenklatura is formed as a result of undemocratic state governance and appointments to positions instead of real elections, its formation can be prevented through maximum democratization and maintaining a high level of democracy — for example, transitioning to a parliamentary system and expanding democratic institutions (we wrote about this here). It is necessary to ensure freedom of the press, change of power, real competition among political parties, strengthening the rule of law, decisive fight against corruption — in short, all the points of genuine democratization.

- Concise Political Dictionary. Moscow, 1964, 1968, 1971

- Party Building. Textbook, 6th edition. Moscow, 1981

- A. D. Sakharov. About the Country and the World. New York, 1975, p. 19

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Dominant Class of the Soviet Union (Second, Revised and Expanded Edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 36.

- Ibid., p. 165.

- N. Porzgen. Ein Land ohne Gott. Frankfurt a. M., 1936, S. 69

- A. Ciliga. Im Land der verwirrenden Luge. Duisburg, 1954, S. 240

- V.I. Lenin. Complete Works. Fifth edition. Vol. 33 (The State and Revolution). Moscow: Publishing House of Political Literature, 1969, p. 24.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- O.B. Mozokhin. Evacuation of the population, industrial facilities, and cultural valuables from the front-line zone during the Great Patriotic War // Journal of Russian and East European Historical Studies, №1(12), 2018

- Automobilization of Russia. Chariot of Fate – Lyudmila Mokhovikova

- “…it would seem that the all-powerful Politburo did not conduct such experiments, and the chairmen of collective farms were confidently appointed by the bureaus of district party committees” // M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Dominant Class of the Soviet Union (Second, Revised and Expanded Edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 122.

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Dominant Class of the Soviet Union (Second, Revised and Expanded Edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 127-128.

- Ibid., pp. 128-133.

- Program of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union // CPSU. 22nd Congress. Moscow, 1961. Materials of the XXII Congress of the CPSU. – 461 pp. – Moscow: Goslitizdat, 1961. – p. 368.

- Pavel Sudoplatov. Intelligence and the Kremlin. Notes of an Unwanted Witness. – 507 pp. – Moscow: TOO “Geya”, 1996. – p. 43.

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Dominant Class of the Soviet Union (Second, Revised and Expanded Edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 311.

- Ibid., pp. 256-257.

- “Pravda”, 25.01.1986

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Dominant Class of the Soviet Union (Second, Revised and Expanded Edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 155.

- Ibid., pp. 120-121.

- M.S. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Dominant Class of the Soviet Union. – 624 pp. — Moscow: “Soviet Russia” jointly with MP “October”, 1991. – p. 597.

- Ibid., pp. 595-596.