What Is Social Democracy?

Our journal identifies itself as social democratic, and in light of this, it becomes especially important to clearly define what social democracy means and what the term encompasses. This question is crucial not only for shaping our political identity and understanding our position on the political spectrum, but also for distinguishing ourselves from other movements. In this article, we aim to provide an answer.

We have arrived at the core question our journal seeks to address: what is social democracy, and who are social democrats? Starting with widely accepted brief definitions, social democracy is an ideological and socio-political movement rooted in the labor and democratic movements, aiming to achieve social justice1. That was the definition from the Great Russian Encyclopedia, while Merriam-Webster provides two definitions2:

- a political movement advocating a gradual and peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism by democratic means;

- a democratic welfare state that incorporates both capitalist and socialist practices.

Britannica explains this divergence as follows: social democracy is a political ideology that initially advocated for a peaceful, evolutionary transition from capitalism to socialism by means of established democratic processes. In the second half of the 20th century, a more moderate version of the doctrine emerged, which primarily supported state regulation (rather than state ownership of the means of production) and extensive welfare programs3.

Today, it would be more accurate to say that the first Merriam-Webster definition corresponds to the concept of «democratic socialism» (which we will discuss later). What we now refer to as social democracy aligns more closely with what Britannica describes as the «more moderate version» — a political ideology that uses democracy and state regulation to build a welfare state based on the principle of universal well-being.

Given that traditional social democracy today lacks a coherent theoretical framework, and that the new millennium threatens serious problems (such as the rise in inequality, described in the works of Thomas Piketty4) and new challenges, the journal «Logic of Progress» seeks to formulate the foundations of a new movement capable of responding to these challenges — progressive social democracy.

Contents

History of Social Democracy

The history of the global social democratic movement is far too vast to fully explore here; it deserves a separate article. In this section, we will offer only a very brief overview. It is commonly believed that social democracy emerged under the influence of socialist ideology (such as utopian socialism) and Marxism. However, if we refer to the definition we formulated earlier, the history of social democracy may be much broader, possibly including figures of the French Revolution — or even Pericles.

Nonetheless, the term «social democracy», as noted in the Friedrich Ebert Foundation’s publication, first appeared and began to be used within the «Workers’ Brotherhood» led by Stephan Born — members of this organization in the late 1840s were the first to call themselves social democrats5. The term came into widespread use with the founding of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1863. At that time, the party was led by Ferdinand Lassalle and was also under the ideological influence of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. After the founding of the Second International in 1889, it became a model for many other social democratic parties.

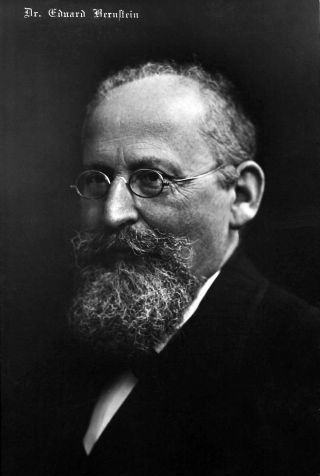

In the late 19th century, Eduard Bernstein developed the idea that social justice should be achieved not through revolution but through reform. He emphasized the process of movement toward socialism over the goal itself. In practice, this meant moving away from revolutionary barricades and toward democratic political struggle. Over time, this led to a split within the movement — between social democrats and communists — most clearly seen in Russian social democracy, with the division between the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks.

Meanwhile, Bernstein’s concept proved effective, and social democratic parties began to gain power, as we discussed in the relevant article.

As communists began to label social democrats as enemies of the working class and agents of capital (for example, Joseph Stalin stated that «you cannot defeat capitalism without first defeating social democracy within the labor movement’6) and dismantled democracy (and social democratic organizations) wherever they came to power, establishing one-party dictatorships, tensions between the two movements grew. However, facing fascist and Nazi threats, temporary alliances were formed in the shape of Popular Fronts.

After World War II, social democrats — having gone through a severe crisis in the 1930s — emerged as a powerful global socio-political force. Following the Kravchenko trial in 1948, which exposed the inhuman nature of Stalin’s regime, it was the communist parties — whose ideas had enabled Stalin’s rise — that entered into a deep crisis, first in Europe and later globally. Eventually, communists ceased to be a significant political force, and social democrats became the recognized vanguard of the leftist movement.

This transformation was made possible because, after WWII, social democrats led governments or took part in ruling coalitions in many countries, achieving considerable success in building welfare states. Beginning in 1959, with the adoption of the SPD’s Godesberg Program, social democratic parties started to distance themselves from Marxism (mainly due to its obsolescence), often shifting their focus from «socialism» to the realization of universal human values.

Communist states, by contrast, experienced economic and political collapse, with widespread human rights abuses and poor living conditions exposed — while social democrats were achieving real successes. In the 1980s, conservatives temporarily regained influence, particularly in the UK and the US, by promoting free market policies through the reforms of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. However, in the 1990s, the social democratic movement recovered and returned to power in most Western countries.

Today, we are witnessing conservative attempts at a counteroffensive, this time relying on nationalist rhetoric.

Core Principles of Social Democracy

At the core of every political movement lie its declared values — its theory and practice are built around realizing them in the most effective way. As noted in the textbook «Foundations of Social Democracy»: «Social democracy, on a normative level, is guided by core values and fundamental human rights and freedoms… Today, we generally speak of three fundamental values: freedom, equality/justice, and solidarity»7.

We addressed the issue of freedom and tolerance in a dedicated article, where we explained that freedom does not mean the ability to do whatever one pleases — it is constrained by law. The issue of equality and justice was covered here. Based on various authors, solidarity can be briefly defined as follows8:

- A collective, mutual sense of responsibility based on shared interests;

- Expressed through behavior that serves the common good, even when it does not align with one’s short-term self-interest;

- Goes beyond formal claims to mutual fairness.

Our journal expands and clarifies the list of values: we present them in the article on progressive values. These values serve as the foundation of progressive social democracy. In our view, they provide a more complete strategic framework for contemporary social democratic politics.

In political terms, social democrats support the core principles of democracy — which we listed in this article. Progressive social democrats go further, advocating for professional councils and exploring new ways to deepen democratization.

In economic terms, social democrats support a mixed economy (also known as a «coordinated market economy»), the welfare state, progressive taxation, and the development of manufacturing and/or innovative industries. Progressive social democrats add to this by expanding the principles of progressive taxation and the welfare state, and by introducing additional elements — we outlined the overall vision of such an economy here.

Social democrats support a secular state, the fight against racism and xenophobia, and gender equality. As for acquiring the tools needed to implement these reforms, social democrats aim to gain power through democratic means. In authoritarian states, they focus on undermining monolithic rule and cooperating with democratic movements through broad coalitions. (In cases where the regime is completely unwilling to compromise, revolutionary change may also be possible.)

At the same time, one of the strengths of social democracy is its lack of dogmatism and its ability to adapt and respond effectively to modern challenges. The authors of «Foundations of Social Democracy» emphasize this:

The path of social democracy — both as an idea and a political action program — must be constantly scrutinized, adjusted, and reconsidered if it is to succeed.

Social democratic discourse has always been characterized by constant motion, awareness of social development trends, assessment of opportunities and risks, and using those assessments to guide political direction. This is what sets social democracy apart from other political models: it does not cling to old foundations but remains open to new realities and new challenges9.

Social Democrats’ Attitude Toward Other Ideologies

As a rule, social democrats are hostile to ideologies that do not accept the democratic «rules of the game» — that seek to concentrate all political power in their own hands and deprive others of the ability to participate in elections. Most commonly, this refers to communists, fascists, Nazis, supporters of absolute monarchy and authoritarianism, and certain anarchists and libertarians who advocate abolishing the system of representative democracy (we explained in detail here why we do not view direct democracy as an adequate alternative). These are the primary political opponents of social democrats. In our articles on democracy, power rotation, and inclusive institutions, we explained why democracy is necessary and positively impacts quality of life, whereas most dictatorships lead to poverty and human rights violations.

Social democrats take a more reserved stance toward movements that share democratic principles and recognize the right of their opponents to participate in fair elections, form governments, and so on (even if they are not left-leaning). This includes certain liberals and national democrats (democratic movements are discussed in more detail in the article listing ideologies). Broad coalitions for overthrowing an authoritarian regime may be possible with them, but governing coalitions are unlikely.

Finally, social democrats typically form allied relationships with social liberals and Greens, as well as with democratic socialists and Christian democrats. Communists and anarchists may be included in parliamentary coalitions with social democrats, but only if they are moderate and only in the role of junior partners.

Difference from Democratic Socialism

Although many social democratic parties still declare the achievement of socialism — now called democratic socialism — as their goal (for instance, the German SPD states that this means «a society in which freedom, justice and solidarity are truly dominant»10), not all social democrats share this objective.

The main reason is that a goal like «socialism» can overshadow the core goal of realizing progressive values. Moreover, no one knows precisely what this “socialism” would look like, leaving room for widely varying interpretations. We have the Soviet experience, where the system built during the Stalin era was labeled «socialism» (in 1936, Joseph Stalin stated that “we have, in the main, already achieved the first phase of communism, socialism”11), effectively proclaiming the goal accomplished, even though progressive values were only marginally realized and human rights were grossly violated. By substituting the values with a vague end goal like “socialism”, we risk repeating past mistakes. If an incorrect definition of socialism becomes dominant (and bad-faith actors may push for this — no movement is immune to such individuals), we’ll be pursuing the wrong goal, leading us into a dead end. Furthermore, as we discussed in our article on economic systems, socialism is usually understood to mean the absence of private ownership of the means of production — a notion that contradicts research supporting the necessity of private ownership.

Therefore, progressive social democrats do not set such a final goal for themselves (among the goals, albeit not final ones, are implementing the Fourth Industrial Revolution and building the city of the future). Social democracy, as such, does not have a fixed endpoint — its development may be endless, adapting differently to the unique challenges of each era. As Foundations of Social Democracy notes, «social democracy cannot be built once and for all; it cannot be achieved in a single moment like a 100-meter sprint»12. We do not know how productive forces will evolve in the distant future and how that will affect the requirements for a just society — therefore, we should not attempt to design it now without the necessary knowledge. Democratic socialists, however, set the goal of achieving “socialism”, even though they don’t know what it would entail. This is the key difference between social democrats and democratic socialists. For example, based on the writings of democratic socialists in Jacobin, it is clear that their idea of democratic socialism necessarily involves reducing the share of private ownership13, while concerns about how this affects human welfare seem secondary. When redistribution of property matters more to people than how it impacts quality of life, it raises suspicions about their true motives.

As renowned economist Daron Acemoglu points out, democratic socialism is often confused with social democracy: the latter does not imply nationalizing production. In his view, deviations from the social democratic compact — either toward democratic socialism and collectivized production or toward deregulated markets — result in negative economic outcomes14. He concludes: «Social democracy beats democratic socialism».

Whose Interests Does Social Democracy Represent?

It is traditionally believed that the primary social force social democrats rely on is the working class — that is, the group of wage laborers in the sphere of material production and services that emerged in industrial society15. History has also shown that social democracy draws support from the left-wing segment of the intelligentsia. Even Vladimir Lenin noted that Marx and Engels, who were social democratic figures, belonged to the intelligentsia:

The socialist doctrine grew out of those philosophical, historical, and economic theories developed by educated representatives of the propertied classes, by intellectuals. The founders of modern scientific socialism, Marx and Engels, themselves belonged by social position to the bourgeois intelligentsia16.

From modern social democratic programs, we can also identify other groups whose interests are represented. For example, small businesses — thanks to the fact that progressive taxation shifts the burden from small businesses to large capital, creating more favorable conditions for small entrepreneurs (including through the enhancement of the rule of law and the achievement of social consensus as a guarantor of stability). Another such group includes the unemployed and people unable to work, whose interests are addressed through the welfare system. In the article on the allies of social democrats, we also list other social groups and movements whose interests are represented and implemented by social democrats. A new and growing group is freelancers. Since their income is unstable and often lacks pension or social security guarantees, the social democratic idea of an unconditional basic income gives them a greater sense of security about the future.

Social democratic policies sharply conflict with the interests of the elites — large capital and the nomenklatura. Large capital is dissatisfied with the taxation policy promoted by social democrats, their support for trade unions, and other high standards that hinder profit maximization. Therefore, its representatives often support libertarians, liberal conservatives, or even racist movements that help incite division among wage workers. The nomenklatura, in turn, opposes the principles of democratic turnover and elected governance demanded by social democrats, as these principles obstruct efforts to turn political power into a stable source of personal income. For this reason, it usually supports fascists, communists, and other movements that advocate dictatorship.

Right-liberal ideologies focus on the fulfillment of individual interests; conservative and communist ones — on the interests of society as a whole. The former contain an internal contradiction, since one person’s interests may conflict with another’s. The latter, in practice, lead to certain groups passing off their private interests as public good and enforcing them — this is due to the presence of self-interested individuals in society, which is practically impossible to eliminate. The social democratic concept, by contrast, is based on achieving a balance between individual self-interest and the public good, bringing both to a common denominator17.

Which Parties Can Be Considered Social Democratic

Today, social democratic parties are those that share the modern values of social democracy. That is, nationalist parties or those that claim Marxism as their ideology should not be considered social democratic today. Justifying military aggression, human rights violations, or endorsing figures associated with such actions is unacceptable for social democrats. Likewise, parties with a religious orientation should not be included in this category.

It is also incorrect to classify various types of political «spoilers» as social democratic parties—this term refers to parties or candidates with little or no chance of winning, but who can prevent a rival from succeeding18. These are often artificially created to control the political field (for example, the party «A Just Russia»19), or are remnants of former communist nomenklatura that have adopted the label «social democrats» without actually aligning with its principles.

Properly social democratic parties are those that advocate for reducing inequality (and implement such policies when in power), support progressive taxation, promote economic development (particularly in manufacturing and/or innovative sectors), and oppose racism and authoritarianism. This is the minimum set of requirements.

Which Countries Can Be Considered Social Democratic

Since social democracy excludes dictatorship, a country does not have to be continuously governed by social democrats to be considered social democratic. A country where a strong social democratic party has existed for a long time, frequently takes part in forming governments, and influences policymaking, can be classified as social democratic.

Social democratic countries often feature a two-party system dominated by a social democratic and a liberal party.

Accordingly, the longer a social democratic party exists and participates in government formation in a country—and the more it aligns with the above criteria—the more social democratic that country can be considered. The best examples are the Nordic countries (to a lesser extent, Iceland). Germany, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Belgium, Austria, Switzerland, and Spain can also be included. There are also several countries that can be described as almost social democratic.

- Social Democracy // Great Russian Encyclopedia. Volume 30. Moscow, 2015, pp. 748–749. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://bigenc.ru/world_history/text/3638953 (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- Social democracy // Merriam-Webster (www.merriam-webster.com). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/social%20democracy#learn-more (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- Social democracy // Encyclopedia Britannica (www.britannica.com). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.britannica.com/topic/social-democracy (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- Thomas Piketty. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. – 592 p. – Moscow: Ad Marginem Press, 2015.

- Michael Reschke, Christian Krell, Jochen Dahm et al. History of Social Democracy – p. 27 // Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (www.fes.de). [Electronic resource]. URL: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/10390.pdf (accessed: 17.10.2020).

- J. V. Stalin. Collected Works. Volume 10. August–December 1927. – 399 p. – Moscow: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1949. – p. 250.

- Tobias Gombert, Julia Bläsius, Christian Krell, Martin Timpe. Foundations of Social Democracy, p. 10 // Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (www.fes.de). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/akademie/07650.pdf (accessed: 14.10.2020).

- Ibid., p. 37.

- Ibid., p. 145.

- Ibid., p. 81.

- J. V. Stalin — Report to the Extraordinary 8th All-Union Congress of Soviets

- Tobias Gombert, Julia Bläsius, Christian Krell, Martin Timpe. Foundations of Social Democracy – p. 87. // Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (www.fes.de). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/akademie/07650.pdf (accessed: 14.10.2020).

- Michael A. McCarthy. Democratic Socialism Isn’t Social Democracy // Jacobin Magazine (www.jacobinmag.com). July 8, 2018. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/08/democratic-socialism-social-democracy-nordic-countries (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- Daron Acemoglu. Social Democracy Beats Democratic Socialism // Project Syndicate (www.project-syndicate.org). February 17, 2020. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/social-democracy-beats-democratic-socialism-by-daron-acemoglu-2020-02/russian?barrier=accesspaylog (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- D.O. Churakov. Working Class // Great Russian Encyclopedia. Vol. 28. Moscow, 2015, pp. 108–110. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://bigenc.ru/domestic_history/text/3488091 (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- V.I. Lenin. Collected Works. Fifth Edition. Volume 6. January–August 1902. – 619 pages. – Moscow: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1963. – pp. 30–31.

- Tobias Gombert, Julia Bläsius, Christian Krell, Martin Timpe. Foundations of Social Democracy – p. 85. // Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (www.fes.de). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/akademie/07650.pdf (accessed: 14.10.2020).

- Spoiler // Merriam-Webster (www.merriam-webster.com). [Electronic resource]. URL: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spoiler (accessed: 15.10.2020).

- Evgeny Dubrovin. The Decline of “A Just Russia”: Meduza tells the story of Sergey Mironov, who tried to create a second “party of power” in Russia but was punished // Meduza (meduza.io). August 28, 2019, 15:41. [Electronic resource]. URL: https://meduza.io/feature/2019/08/28/sbrod-v-horoshem-smysle-slova (accessed: 15.10.2020).