Joseph Stalin’s coup d’état

In official Russian historiography, it is not customary to question the “natural” rise of Joseph Stalin as the dictator of the state. Almost no attention is paid to the fact that, in essence, a coup took place: first within the Politburo in the late 1920s, and later, in 1937–1938, within the entire party. During this process, a conservative group led by Joseph Stalin came to power—something quite different from the Bolshevik Party itself. These facts suggest that equating Stalin’s dictatorship with the Bolsheviks’ collective leadership is a mistake: the two political forces had significant differences.

If someone had claimed back in 1922 that Joseph Stalin would become the leader of the party and the country, few people would have taken it seriously; most would have considered it a joke. It was hard to believe that this far from gifted, yet persistent and proactive party member could reach any truly commanding heights. How, then, did Stalin — who lacked the economic acumen of Nikolai Bukharin, the status of founder of the Red Army like Leon Trotsky, the authority among workers’ unions like Mikhail Tomsky, the strategic brilliance of a military commander like Mikhail Frunze, and generally none of these notable achievements — manage to acquire unlimited power?

Trotsky called him “the most outstanding mediocrity of our party”1. Lev Kamenev, in turn, would condescendingly shut him up whenever Stalin tried to discuss politics with his friends2. Martemyan Ryutin, once one of his main supporters who organized dispersals of Trotsky’s demonstrations, called him “an utter nobody” and “a schemer”3. Amusingly, it was Stalin’s mediocrity and lack of charisma as a person and political figure that actually helped him in the struggle for the levers of party control, much as it later helped Nikita Khrushchev.

Contents

The Mechanics of a coup: the first stage

Stalin’s rise to power began on April 3, 1922, when he was appointed General Secretary of the Central Committee of the RCP(b). Until his death in 1919, Yakov Sverdlov had held this post and performed its duties admirably, and his loss was particularly hard for the Bolshevik party. As Stalin’s former secretary Boris Bazhanov recalled, the initiative to nominate Stalin specifically came from Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev:

It was very close to Molotov becoming — or rather, remaining — at the head of the party apparatus, which was automatically heading toward power. Zinoviev and Kamenev preferred Stalin over him, and essentially for one reason only — they needed a fierce enemy of Trotsky in that post. Stalin was that4.

We will primarily rely on Bazhanov’s account, as he was one of the few surviving official witnesses to Stalin’s seizure of power after the Great Terror (let us emphasize — unique witnesses, since the work of the Orgburo was considered secret), and he described this process in the most detail, namely the mechanism by which Stalin, starting in 1922, placed “his” people in all key positions of the Soviet state:

With Stalin’s appointment as General Secretary, the Orgburo becomes his main instrument for selecting his people and thereby capturing all local party organizations5.

<…>

Stalin and Molotov were interested in keeping the Orgburo as small as possible — only their own people from the party apparatus. The fact is that the Orgburo carried out work of immense importance for Stalin — it selected and assigned party personnel: first, for all departments in general, which was relatively unimportant, and second, all personnel of the party apparatus — secretaries and key workers of provincial, regional, and territorial party organizations — which was extremely important, since it would secure Stalin a majority at the party congress tomorrow, the main condition for seizing power. This work proceeded at a very energetic pace; astonishingly, Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev, floating in the clouds of high politics, paid little attention. The importance of this would only be understood when it was too late6.

Considering that the Bolsheviks did not understand the importance of parliamentary democracy, it is unsurprising that they were incompetent regarding political organization and the dangers of errors in it. The technique was as follows — the Orgburo under Stalin “recommended” a candidate, and in most cases that candidate was elected, since local organizations trusted the Central Committee and rarely opposed it. We find confirmation of this technique in the work of a leading researcher of the Soviet nomenklatura, Mikhail Voslensky:

Leadership positions in party committees were, according to the party statute, elective. A way to bypass this provision of the statute was easily found: leading party bodies “recommended” to lower-level bodies the individuals to be elected. For example, candidates for secretaries of volost party committees were recommended by the provincial committee; candidates for secretaries of provincial committees were recommended by the Secretariat of the Central Committee. The Secretariat carried out intensive work to select and reassign these new governors: in 1922, 37 provincial secretaries were moved and 42 new ones “recommended”. Significantly, the same Secretariat of the Central Committee recommended candidates not only to lower-level but also to higher-level bodies — the Orgburo of the Central Committee, which made decisions on filling the highest posts in the party and the state. In this way, the Secretariat, led by Stalin, centralized in its hands the appointment of the most responsible leadership positions in the country7.

Bazhanov also detailed the role of the Central Control Commission of the VKP(b) as a tool in the struggle for power — any minor misstep by opposition representatives was a pretext for Stalin’s people to send information to the CCC and remove an undesirable cadre, replacing them with their own8, while Stalin’s supporters were, on the contrary, forgiven almost anything (this practice later became one of the causes of mass denunciations during the “Great Terror” — Stalin’s supporters believed that each new denunciation would free up a place in power for themselves or their people). Bazhanov’s account is corroborated by former Lieutenant-General of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs Pavel Sudoplatov, who cites the words of Anna Tsukanova, deputy head of the Department of Leading Party Bodies, in a private conversation:

I was strongly impressed by Anna’s words that the Central Committee did not always take action on reports of bribery, “corruption”, etc., from the Party Control Commission and security agencies. Stalin and Malenkov preferred not to punish loyal high-ranking officials. If, however, they were considered rivals, the compromising material was immediately used for their dismissal or repression9.

Another of Stalin’s “tricks” was to propose expanding the membership of a committee10, say, from 27 to 40 people, and the 13 new members would be Stalin’s own cadres.

Alongside this work of seizing power, there was also a “shadow” work — the part that was kept maximally secret from the early 1930s, and after the “Great Terror”, there were no witnesses left inside the country. We will discuss this part later. For now, we have considered the first stage — how Stalin placed his people at the lower levels of the administrative system. But there were also people at the top, and these were serious figures — Trotsky, Bukharin, Kamenev, and Zinoviev, and they could not be easily displaced. These were major authorities within the Bolshevik party, and if they united, Stalin would simply be pushed into third-tier roles. Therefore, everything had to be done with maximum caution here.

Second stage: weakening Trotsky

The second stage was to weaken the position of Lev Trotsky. After Lenin’s death, Trotsky became perhaps the most popular, well-known, and influential political figure in the Soviet Union. Even during Lenin’s lifetime, he sought to encourage the creation of a “troika” in opposition to him — Kamenev, Zinoviev, and Stalin — each of whom could not individually compare in stature to the People’s Commissar for Military Affairs, but together they wielded comparable influence. This allowed for collective leadership, which served as a safeguard against the concentration of power in the hands of a single figure. Stalin decided to exploit the fears of Zinoviev and Kamenev that Trotsky’s popularity would make him so powerful that all paths to personal dictatorship would be open to him. Bitterly ironic, but in this case, in choosing the path to avoid such a fate, we encounter it precisely there. The “troika” decided to remove Trotsky from the important post of People’s Commissar for Military Affairs, which would also allow Stalin to remove Trotsky’s trusted allies from the Revolutionary Military Council (Revvoyensovet) and then from other posts. Bazhanov describes the technique of the process:

In September, the troika decided to deliver the first serious blow to Trotsky. Since the beginning of the Civil War, Trotsky had been the organizer and unchanging leader of the Red Army, holding the posts of People’s Commissar for Military Affairs and Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic. The troika planned his removal from the Red Army in three stages. First, the composition of the Revolutionary Military Council had to be expanded, filled with Trotsky’s opponents so that he would find himself in the minority within the council. The second stage involved restructuring the leadership of the War Ministry, removing Trotsky’s deputy Sklyansky, and appointing Frunze in his place. Finally, the third stage was Trotsky’s removal from the post of People’s Commissar for Military Affairs.

On September 23, at the plenary session of the Central Committee, the troika proposed expanding the composition of the Revolutionary Military Council. All newly introduced members were opponents of Trotsky. Among the new members was also Stalin11.

<…>

Finally, in early March, a new plenum dealt another blow to Trotsky: Trotsky’s deputy Sklyansky (whom Stalin hated) was removed; a new composition of the Revolutionary Military Council was approved; Trotsky remained chairman, but Frunze was appointed as his deputy and simultaneously as Chief of Staff of the Red Army. Trotsky’s enemies entered the council en masse: Voroshilov, Unshlikht, Bubnov, and even Budyonny. The decorative post of specialist–commander-in-chief (Colonel of the Tsarist Army Sergey Kamenev) was abolished12.

Trotsky was removed from the most important levers of influence, but Zinoviev and Kamenev, who were as strong as Stalin, remained.

Third stage: weakening Kamenev and Zinoviev

In December 1925, the 14th Party Congress was scheduled to take place, where Stalin would be able to fully deploy his cadres and take complete control of power:

By putting Stalin forward in the spring of 1922 for the post of General Secretary of the party, Zinoviev believed that the positions he himself held in the Comintern and the Politburo were clearly more important than the position at the head of the party apparatus. This was a miscalculation and a misunderstanding of the processes occurring within the party, which were concentrating power in the hands of the apparatus. In particular, one thing should be absolutely clear to those fighting for power: to be in power, one needed a majority in the Central Committee. But the Central Committee is elected by the party congress. To elect your own Central Committee, you needed to have a majority at the congress. And to achieve this, you needed the support of the majority of delegations at the congress from provincial, regional, and territorial party organizations. Meanwhile, these delegations are not so much elected as selected by the leaders of the local party apparatus — the provincial committee secretary and his closest associates. By selecting and placing your own people as secretaries and key workers of the provincial committees, you will secure your majority at the congress13.

This is exactly what happened: at the 14th Congress, Stalin’s group began the attack on the “Leningrad Opposition” (Zinoviev was chairman of the Leningrad Soviet Executive Committee), and although Zinoviev and Kamenev retained their posts, their authority declined. When Kamenev attempted to speak at the congress “against creating a leader”14, Stalin’s appointees interrupted him with shouts and protests.

Before the congress, Kamenev and Zinoviev had counted on the support of the Moscow organization, but its first secretary, Nikolai Uglanov, whom Zinoviev trusted, suddenly switched to Stalin’s side, which predetermined the complete defeat of Zinoviev’s faction. Bazhanov provides a detailed account of Uglanov’s betrayal and his “processing” by Stalin15.

After the 14th Congress in 1926, Zinoviev was removed from the post of chairman of the Leningrad Soviet Executive Committee and the Comintern Executive Committee, Kamenev from the posts of chairman of the Moscow Soviet Executive Committee and chairman of the Council of Labor and Defense; in the same year, they and Trotsky were removed from the Politburo. In their place were introduced individuals personally loyal to Stalin — Voroshilov and Molotov — as well as the fully manageable Kalinin and Rudzutak.

Fourth stage: crushing the left opposition

All these maneuvers, while increasing Stalin’s political influence, still did not give him complete power. The system established during Lenin’s lifetime was by no means the strongest, but neither was it the most fragile. Had Trotsky’s and Bukharin’s supporters united and acted in concert, they could have removed the General Secretary. But while Stalin and Zinoviev were preoccupied with questions of personal power and backstage intrigues, other Leninist supporters were more concerned with ideological issues and implementing new domestic policies. Within the USSR, industrialization needed to be carried out, while the country was technologically backward, weakened by wars, and lacked sufficient resources for modernization. The international political situation was also tense — in 1922, the first fascist regime was established in Italy, and there was also a risk of anti-communist uprisings supported by the democratic countries that had recovered from World War I.

In 1925, the economist Evgeny Preobrazhensky, who had been working on solutions to economic problems and was co-author with Bukharin of the «ABC of Communism», completed his work «The Fundamental Law of Socialist Accumulation», in which he criticized the NEP16. He proposed the creation of a state industrial monopoly trust that would carry out socialist accumulation for a major leap forward at the expense of “pre-socialist” forms of the economy, primarily the peasantry. At that time, the Bolsheviks gradually began splitting into two camps — supporters of accelerated industrialization and supporters of the NEP. Preobrazhensky and Bukharin, once co-authors of the «ABC of Communism», now found themselves on the ideological frontlines of two opposing ideas.

As early as April 1926, at a plenary session of the Central Committee, discussions began on a party program for the industrialization of the country. In contrast to the cautious report by Alexei Rykov, which envisaged slow industrialization, Trotsky proposed a plan for accelerated industrialization (based on Preobrazhensky’s work), for which resources would need to be extracted from agriculture1718. Kamenev and Zinoviev sided with Trotsky. The “United Opposition” was formed, which proposed to increase the tax pressure on peasants and NEPmen, and ensure rapid growth of heavy industry19. Essentially, they proposed only a more resolute taxation of the upper layers of the peasantry. They also planned to take loans from the peasantry, invest the money in industry, and reduce the cost of goods.

The ideological leader in the fight against Trotsky was Bukharin, who, together with Rykov and Tomsky, formed the “right wing” of the Politburo. Everything depended on which side the Stalinists would take. In the course of disputes with the opposition, Stalin sided with Bukharin — that is, against forced industrialization at the expense of the peasantry! Contrary to the attempts of Stalinists to present him as the main ideologist of forced industrialization, in a report to the Leningrad Party organization on the work of the CC plenum on April 13, 1926, “On the Economic Situation of the Soviet Union and the Party’s Policy”, Stalin stated:

In our party there are people who consider the working masses of the peasantry as a foreign body, as an object for exploitation by industry, as something like a colony for our industry. These people are dangerous, comrades. The peasantry cannot be for the working class either an object of exploitation or a colony. Peasant agriculture is a market for industry just as industry is a market for peasant agriculture. But the peasantry is not only a market for us. It is also an ally of the working class20.

The outcome of the struggle against the “United Opposition” was that the 15th Congress of the VKP(b) approved the decision of the joint meeting of the CC and CCC to expel Trotsky and Zinoviev from the party. By a resolution on the opposition adopted on Stalin’s report, the congress also expelled 75 other “active members of the Trotskyist opposition”, including prominent figures such as Kamenev, Pyatakov, and many others21. However, Bukharin still remained, whose ideological position Stalin had adopted in the fight against the “Trotskyists”. Now it was necessary to remove him.

Fifth stage: crushing the right opposition

Stalin was very afraid of Trotsky, and on January 17, 1928, Trotsky was forcibly taken to Yaroslavsky railway station and exiled far away — to Alma-Ata22. Now, with Trotsky posing no threat, Stalin simply appropriated the slogans of the “Left Opposition” and advocated accelerated industrialization at the expense of the countryside, while the position he himself had recently held was declared the “right deviation”. This meant that Bukharin and his allies in the Politburo — Rykov and Tomsky — were the next targets. On September 18, 1928, an article by Stalin, “The Comintern on the Struggle Against Right Deviations”, was published in «Pravda». The report on the danger of the “right deviation” was read by Stalin at the Plenum of the Moscow Committee and the Moscow Control Commission of the VKP(b) in October 1928. At the April Plenum of the CC and CCC (1929), Stalin stated about Bukharin: “Yesterday still personal friends, now we differ in politics”. The Plenum completed the “defeat of Bukharin’s group”, and Bukharin himself was removed from his posts. In November 1929, he was expelled from the Politburo; in 1930, the same happened to Rykov and Tomsky.

On December 21, 1929, Stalin’s 50th birthday, the Soviet press was filled with flattering panegyrics in his honor23, and this date can be considered the beginning of both his cult of personality and his personal dictatorship. Martemyan Ryutin recalled that “for any Bolshevik who had not yet completely lost his sense of shame and had not forgotten old party traditions, the whole comedy of the ‘coronation’ caused feelings of disgust and shame for the party”24. From the April Plenum onward, Stalin finally obtained what he had wanted — the supreme personal power.

Sixth stage: 1937

However, already after the party members saw Stalin implementing the “Left Opposition” program, many realized that the General Secretary lacked both the ability and talent to successfully carry out this program. Viktor Serge recalls:

From 1928–1929, the Politburo adopted the main ideas of the excluded opposition — of course, except for workers’ democracy — and implemented them with ruthless cruelty. We proposed taxing wealthy peasants — they are eliminated! We proposed restrictions and changes to the NEP — it is abolished! We proposed industrialization — it is carried out at furious “super-industrialization” rates25.

Even former supporters of Stalin, Ryutin and Uglanov, campaigned against him, and among the “old Bolsheviks”, dissatisfaction with the General Secretary’s policies grew. Stalin, being a very suspicious and cowardly man (it is enough to recall that in October 1917, very little information exists about his activity), feared his overthrow and prepared the final stage of his state coup — the “Great Terror”, which would mostly occur in 1937-1938. This is a separate story that requires detailed treatment. During this terror, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky, Uglanov, Preobrazhensky, and Ryutin — all those with any political weight — would be eliminated.

Stalin could clearly see how the bureaucrats he had nurtured, filled with malicious envy, looked at the alien and disagreeable aging Leninists, who still retained traces of convictions beyond the understandable desire of the Stalinists to occupy higher posts, enjoy power, and a good life. Stalin realized that only a signal was needed — and his protégés would pounce like a wolf pack and tear the throats of these weak, and therefore illegitimately holding leadership positions, old eccentrics.<…>

Stalin fulfilled the will of his appointees, leading them to crush the Leninist guard. There was nothing heroic in this campaign. One can have different opinions about the members of the organization of professional revolutionaries created by Lenin. But the reprisal against them was disgusting26.

The dark sides of the rise to power

It would be wrong to think that the Great Terror was simply a temporary lapse that befell Stalin. The General Secretary always used such unscrupulous methods to solve his personal tasks. Boris Bazhanov described how party elections were falsified under Stalin’s instructions:

While speeches were being made at these heights, Stalin remained silent, puffing on his pipe. Actually, Zinoviev and Kamenev were not interested in his opinion — they were convinced that Stalin’s view on political strategy was of no interest at all. But Kamenev was a very polite and tactful man. So he asked, “And you, Comrade Stalin, what do you think on this matter?” — “Ah”, said Comrade Stalin, “on which matter exactly?” (Indeed, many questions had been raised). Kamenev, trying to condescend to Stalin’s level, said, “On the question of how to gain a majority in the party”. — “You know, comrades”, said Stalin, “what I think about this: I believe it is completely unimportant who votes and how in the party; but what is extremely important is who counts the votes and how”. Even Kamenev, who should have known Stalin by now, cleared his throat expressively.

The next day, Stalin summoned Nazaretyan to his office and consulted with him for a long time. Nazaretyan left the office looking rather sour. But he was an obedient man. On the same day, by decree of the OrgBureau, he was appointed head of the party department of «Pravda» and began work.

Reports from party organization meetings and voting results, especially in Moscow, were sent to «Pravda». Nazaretyan’s work was very simple. At the meeting of such-and-such cell, for the Central Committee voted, say, 300 people, against — 600; Nazaretyan transmits: for the Central Committee — 600, against — 300. And that is how it is printed in «Pravda». And so for all organizations. Of course, a cell, reading the false report in «Pravda» about its voting results, would protest, call «Pravda», demand the department of party life. Nazaretyan would politely respond, promising to immediately check. Upon verification, it turned out “you are completely right, an unfortunate mistake occurred, it was mixed up at the printing house; you know, they are very overloaded; the editorial office of «Pravda» apologizes; a correction will be printed”. Each cell believed that this was an isolated error, occurring only with them, and did not suspect that it was happening in the majority of cells. Meanwhile, gradually a general picture was created that the Central Committee was beginning to win across the board. The provinces became more cautious and started following Moscow, that is, the Central Committee27.

When these manipulations were revealed, Stalin blamed Nazaretyan (his long-time friend, one of the few who addressed him informally as “ty”) and removed him from the secretariat and «Pravda», and in 1937 had him executed (Nazaretyan’s wife was arrested with an infant and sent to a labor camp for 17 years)28.

But election falsifications were one of the most benign things Stalin was accused of. Bazhanov writes that Stalin had a special “secretary for dark affairs” — Grigory Kanner (executed in 1938), whom Bazhanov suspected of killing Trotsky’s deputy, Efraim Sklyansky, who died under mysterious circumstances29. According to Bazhanov, the same Kanner organized the medical operation during which Mikhail Frunze died30. Many contemporaries suspected that Frunze’s death was Stalin’s doing, which Boris Pilnyak described in his «Tale of the Unextinguished Moon» (executed in 1938).

Perhaps it is as it should be, that old comrades go so easily and so simply into the grave31.

As historian Roy Medvedev notes, “Of course, neither the people nor the party needed this. But it turned out to be very important for Stalin, as Frunze’s post as People’s Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs was filled by K.E. Voroshilov”32. Bazhanov detailed how Kanner, under Stalin’s orders, installed wiretaps in the automatic network (“screws”) used for communication among government members — including accusing a Czechoslovak technician-communist who installed the network of espionage and his subsequent rapid execution33. According to Bazhanov, all these operations were carried out by Kanner in cooperation with Genrikh Yagoda (executed in 1938).

State coup: the facts

We have the following facts at our disposal:

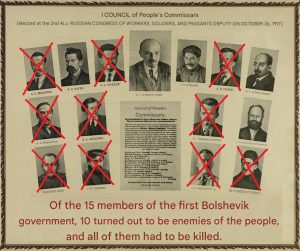

- 5 out of 6 people mentioned by Lenin in his “Letter to the Congress” — that is, those figures whom Lenin considered particularly important for the party — were declared traitors and eliminated: Bukharin, Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Pyatakov. At the same time, it is somewhat illogical that only one “traitor” was spared — Stalin;

- Rykov and Tomsky, who were members of Lenin’s last Politburo (along with Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev, Lenin, and Stalin), were also eliminated during the Great Terror (Tomsky shot himself upon learning that an investigation had been launched against him);

- Out of 139 members and candidate members of the 1934 Central Committee, 110 were killed or driven to suicide34. Of the 1,966 delegates at the 17th Party Congress in 1934, 1,103 were arrested on charges of counter-revolutionary crimes, of whom 848 were executed35.

All of this data indicates that Stalin carried out a coup d’état — that is, the Bolshevik party lost power, ceding it to Stalin’s conservative faction.

What are the proofs that this was a state coup:

- A radical replacement of the country’s leadership;

- Radical changes in the value system of state policy;

- Radical changes in the economic system of the state;

- Testimony of a witness (Boris Bazhanov), including about the use of illegal methods;

- Mass elimination of other witnesses;

- Mass elimination of the most important figures of the Bolshevik party;

- Lack of direct continuity between the country’s leaders (Vladimir Lenin in his “Letter to the Congress” recommended removing Stalin from the position of General Secretary).

This might have been insufficient in a country with a free press, where we could have heard the testimony of many more witnesses, but in relation to Stalin’s USSR, this evidence is more than sufficient. This idea itself is not new, and even the most informed contemporaries, such as Nobel laureate Lev Landau and physicist Moisey Korets, in 1938 distributed a leaflet that began with these words:

Comrades!

The great cause of the October Revolution has been treacherously betrayed. The country is flooded with streams of blood and filth. Millions of innocent people have been thrown into prisons, and no one can know when their turn will come. The economy is collapsing. Famine is approaching. Don’t you see, comrades, that Stalin’s clique has carried out a fascist coup? Socialism now exists only on the pages of utterly deceitful newspapers. In his frenzied hatred of genuine socialism, Stalin has equaled Hitler and Mussolini36.

Similar testimony is provided by Mikhail Voslensky:

At the height of this madness, in the terrifying spring of 1938, when newspapers howled about Trotskyists and Bukharinites — fascist spies and saboteurs — and at every Komsomol meeting at school our deskmates, whose parents had been declared “enemies of the people”, delivered penitential speeches, I first heard an assessment of what was happening that sounded as a dissonance in the shrill hysteria. It was expressed by my former classmate Rafka Vannikov, son of the Deputy People’s Commissar of Defense Industry of the USSR Boris Lvovich Vannikov, who later became head of the First Main Directorate — a gigantic top-secret organization that created the Soviet atomic bomb.

We were leaving the assembly hall after the school’s May Day evening when he suddenly said solemnly:

– Have you noticed that over the past year and a half there has been an almost complete replacement of the country’s leadership?

Rafka was a decent guy, but by no means a master of political analysis. The words he spoke were clearly not his own but his father’s — they came from above, from Kremlin circles. This is how cynically and businesslike those circles viewed what was presented to the world as “the exposure of fascist spies” and “measures to eliminate Trotskyists and other double-dealers”!

The Yezhovshchina, which destroyed and impoverished millions of people, was a complex social and political phenomenon. But in the history of the creation of the ruling class in the USSR, it primarily played exactly this role: it carried out a replacement of the country’s leadership37.

It is necessary to write a separate article on how Joseph Stalin pursued a conservative policy, on how the General Secretary destroyed communists; we have material on this. Taken together with all these facts, we have a sufficiently clear conclusion: in 1929 in the Politburo, and in 1937/1938 throughout the entire system of power, a conservative (essentially fascist) state coup took place, and the Bolshevik party was removed from power.

- L.D. Trotsky. My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography. Vols. 1-2. – 624 pp. – Moscow: Panorama, 1991. – p. 486.

- V.D. Kuznechevsky. Stalin: The Mediocrity Who Changed the World

- M.N. Ryutin. I Will Not Kneel / comp. B.A. Starkov. – 351 pp. – Moscow: Politizdat, 1992. – p. 115.

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – p. 24.

- Ibid., p. 33.

- Ibid., p. 32.

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Ruling Class of the Soviet Union (Second revised and supplemented edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 95.

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – p. 35.

- Pavel Sudoplatov. Intelligence and the Kremlin. Notes of an Unwanted Witness. – 508 pp. – Moscow: TOO “Geya”, 1996. – pp. 374-375.

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – p. 41.

- Ibid., pp. 67-68.

- Ibid., p. 86.

- Ibid., p. 166.

- 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Stenographic Report. December 18-31, 1925. – 1038 pp. – Moscow: GIZ, 1926. – p. 275.

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – pp. 188-189.

- Paths of Development: Debates of the 1920s: Articles and Modern Commentary / Comp. E.B. Koritsky. – 254 pp. – Leningrad: Lenizdat, 1990.

- Resolution of the 15th Congress of the VKP(b) “On Guidelines for Drafting the Five-Year Plan of the National Economy”, December 1927 – CPSU in Resolutions and Decisions of Congresses, Conferences, and Plenary Sessions of the CC, Vol. 4: 1926-1929, Moscow 1984, pp. 274-293.

- A.V. Shubin. Leaders and Conspirators: Political Struggle in the USSR in the 1920s–1930s. – 400 pp. – Moscow: Veche, 2004. – pp. 116-120.

- Draft platform of the Bolshevik-Leninist opposition for the 15th Congress of the VKP(b) (Crisis of the Party and Ways to Overcome It) // Communist Opposition in the USSR, 1923-1927 (from the archive of Lev Trotsky in four volumes). Vol. 4 (1927, July-December) / Comp. Yu. Fel’shtinsky. – 280 pp. – Chalidze Publications, 1988. – pp. 128-130.

- I.V. Stalin. Collected Works. Vol. 8. 1926 (January–November). – 405 pp. – Moscow: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1953. – p. 142.

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Resolutions and Decisions of Congresses, Conferences, and Plenary Sessions of the CC (1898–1986). Vol. 4. 1926–1929. 9th ed., revised and supplemented. – 575 pp. – Moscow: Politizdat, 1984. – p. 313.

- G.I. Chernyavsky. Lev Trotsky. – 665 pp. – Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 2010. – pp. 440-441.

- M.N. Ryutin. I Will Not Kneel / Comp. B.A. Starkov. — 351 pp. — Moscow: Politizdat, 1992. — p. 115.

- Ibid.

- Serge V. From Revolution to Totalitarianism: Memoirs of a Revolutionary / trans. from French by Yu.V. Guseva, V.A. Babintsev. – Moscow: Praxis; Orenburg: Orenburg Book, 2001. – 696 pp

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura. The Ruling Class of the Soviet Union (Second Edition, Revised and Supplemented), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 101-102.

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – pp. 76-77.

- Around Stalin: Historical-Biographical Reference / Compilers V.A. Torchynov, A.M. Leontyuk. – 608 pp. – St. Petersburg: Philological Faculty of St. Petersburg State University, 2000. – p. 354.

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – pp. 86-88.

- Ibid., pp. 134-135.

- I.V. Stalin. Works. Vol. 7. 1925. — 423 pp. — Moscow: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1947. — pp. 250-251.

- To the Court of History: On Stalin and Stalinism – Roy Medvedev

- B.G. Bazhanov. Stalin’s Struggle for Power. Memoirs of a Personal Secretary. – 304 pp. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2017. – pp. 55-59.

- S. Cohen. Bukharin: A Political Biography, 1888–1938: Translated from English / General Editor, Afterword, and Commentary by I.E. Gorelov. – 574 pp. – Moscow: Progress, 1988. – p. 407.

- Report of the CPSU Central Committee Commission to the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee on establishing the causes of mass repressions against members and candidate members of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), elected at the 17th Party Congress. February 9, 1956 // ARF. F. 3. Op. 24. D. 489. pp. 23–91. Original. Typescript.

- Izvestiya of the CPSU Central Committee. 1991. No. 3. pp. 146-147

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura: The Ruling Class of the Soviet Union (Second Edition, Revised and Expanded), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 99