Privileges of the soviet nomenklatura

Was there really no significant social stratification in the USSR, with the nomenklatura living modestly and refraining from theft? Or is this simply propaganda from former nomenklatura members, pushed away from the trough and now trying to bring back that era? We have gathered various testimonies about the actual standard of living of Soviet officials — the conclusions we leave to you.

Thanks to the efforts of the remnants of the former propaganda apparatus of the Communist Party (we traced their origins in the article on Stalinism), a stereotype has taken root in society: that high-ranking officials in the USSR lived rather modestly, almost ascetically, had no special privileges, and were severely punished for corruption. However, the very existence of a large number of representative cars produced in the USSR — ZiS, ZiL, and “Chaika” — which an ordinary Soviet worker could never afford, already suggests that something is not quite right with this stereotype. We have already examined what the nomenklatura was in this article. Let us now take a closer look together and decide whether the talk of their privileges and luxurious lifestyle is a myth or reality.

By the way, if you have any doubts, you can take a look at how today’s nomenklatura lives in Putin’s Russia, and you will discover that most of the mechanisms remain exactly the same. And here’s the question — where did they come from?

Contents

- Eyewitness Accounts

- Salaries

- Vacations

- Food

- Public Consumption Funds

- Taxation

- Foreign travel

- Currency exchange rates

- Apartments

- Country Houses

- Cars

- Servants

- Special Stores

- Special children

- Special Country

- Treatment

- Tickets

- Airplanes

- Pensions

- Special privileges of Central Committee secretaries and Politburo members

- Immunity

- Other Privileges

- How the Nomenklatura Justified Their Privileges

- Conclusion

Eyewitness Accounts

The leading researcher on this subject, Mikhail Voslensky — to whom we will most often refer — described in his work «Nomenklatura» the typical representative of the social stratum he studied as follows:

By nature, he is anything but an ascetic. He drinks readily and heavily, mainly expensive Armenian cognac; he eats with great pleasure and well: caviar, sevruga, beluga flank — things obtained in the cafeteria or buffet of the Central Committee. If there is no risk of scandal, he will quickly start a very non-platonic affair. He has the standard hobbies accepted in his circle: first football and hockey, then fishing, now hunting. He takes care to obtain Finnish furniture for his new apartment and to buy scarce books (of course, quite harmless ones) through the Central Committee’s book distribution office1.

Voslensky himself was once part of the nomenklatura, and therefore his testimony in this work is particularly abundant. But how did ordinary Soviet workers and employees view the nomenklatura at the time? Let us read a letter from a communist in Kazan, Nikolaev, published in «Pravda» on February 13, 1986, when the wave of glasnost gave people more courage:

When speaking of social justice, one cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that Party, Soviet, trade union, economic, and even Komsomol leaders at times objectively deepen social inequality by taking advantage of all kinds of special buffets, special stores, special hospitals, and so on… A leader already receives a higher salary in cash. But in everything else there should be no privileges. Let the boss go to an ordinary store with everyone else and stand in line on the same terms — perhaps then the queues, which have become unbearable for all, will be eliminated sooner. Only it is hardly likely that the “beneficiaries of special advantages” will voluntarily give up their privileges…2

And here is a letter from a worker in the Tula region, in the same issue:

Between the Central Committee and the working class there still hovers a sluggish, inert, and sticky “party-administrative stratum” that is not particularly eager for radical change. Some only carry Party cards, but long ago ceased to be communists. From the Party they expect only privileges…3

These words provoked sharp displeasure among the nomenklatura at the 27th Congress of the CPSU later that year. The First Secretary of the Volgograd Regional Committee of the CPSU, Vladimir Kalashnikov, declared:

In pursuit of sensation, under the pretext of “frank conversation”, one must not slander the cadres of some “sluggish, inert, and sticky party-administrative stratum”. It is not hard to understand whom such authors have in mind4.

In fact, by such statements the nomenklatura admitted the existence of the very privileges readers had spoken of, while the Second Secretary of the Central Committee, Yegor Ligachev, delivered a reprimand to «Pravda» at the Congress. The nomenklatura always tried to conceal the fact of its “special” position. Of course, there were other testimonies as well, but they began to appear in the press only during Perestroika. Let us open «Arguments and Facts», issue No. 25 of 1989, where a letter to the editor was published from Dr. P. Gruzdev:

My wife and I are doctors. We have two children. Our combined salary is 140 + 140 = 280 rubles. The subsistence minimum, according to the Soviet press, is 75 rubles per person. Need I comment?.. In my opinion, the “nomenklatura” and the people enjoying privileges are driving my car, living in my dacha, and eating the food of my family. — P. Gruzdev, Moscow5.

Let us emphasize in particular that certain privileges had already been granted to a small circle of Party figures under Vladimir Lenin, but the heyday of the nomenklatura’s luxurious lifestyle came under the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin.

Salaries

– Will there be money under communism?

– The Yugoslav revisionists claim there will. The Chinese dogmatists claim there won’t. We approach the question dialectically: some will, and some won’t.

According to Mikhail Voslensky, while the official average monthly salary of workers and employees in the USSR was 257 rubles (this figure also included the earnings of the nomenklatura), a department head in the Central Committee received 700 rubles plus a thirteenth salary. After calculating the value of some of the state privileges that nomenklatura members received free of charge (which will be described later in this article), Voslensky estimated the difference in monthly income between a Central Committee department head and the average worker as 10:1 — that is, ten times higher6. (The poverty of life in the USSR was usually justified by “equality”, but against that backdrop, such a gap seemed enormous). It was also noted that if a department head had even a modest command of a foreign language, he would receive a 10% salary bonus for “knowledge and use of a foreign language”, even if the knowledge was doubtful and there was no actual use of it at all. There were also additional sources of income:

First of all, these were fees for articles, books, and speeches. An ordinary Soviet author could write like Leo Tolstoy and still find it difficult to get published. For every author, an editorial office kept a so-called card listing Party membership, nationality, education, position, and place of main employment. I myself was an editor and filled out such cards. The policy was simple: those to be published should preferably be members of the CPSU, Russians (other nationalities were possible, but Jews were undesirable), with higher education, and even better with academic degrees — and, of course, ideally if the author held a nomenklatura post. And if, in addition, the main place of employment was the Central Committee of the CPSU or another Party body, then the author could write any nonsense: everything would be rewritten for him, submitted with gratitude for his signature, and he would be paid at the highest fee rate. It was this, and not any special talent of nomenklatura officials, that explains why all of them write articles, and many of them even publish books. It is telling that the highest fees in the USSR were long paid precisely by the Party press: no newspaper paid fees as high as «Pravda», no journal as high as «Kommunist»7.

But more often, the main source of income for the nomenklatura was corruption. In the USSR its scale was so vast that it requires a separate study, and we already have an article on the heyday of corruption under Joseph Stalin.

Vacations

For a Central Committee official, annual vacation lasted 30 days, plus the travel time to and from the resort. For ordinary Soviet citizens, it was 12–18 days per year. Voslensky noted about a Central Committee department head: “He spends no money at all on medical treatment or on vacation. He is given a free month-long voucher to a sanatorium of the Central Committee or the Council of Ministers. A voucher to the same sanatorium is provided to his wife at a substantial discount, and the children are sent to an excellent Central Committee Pioneer camp8”.

Sanatoriums for high-ranking Soviet officials were marked by modern amenities, luxury attributes, comfort, and the absence of queues or overcrowding. You can easily find information online about the “Pushkino” sanatorium, the CPSU Central Committee sanatorium named after the 17th Party Congress, the “Novye Sochi” sanatorium, and many others. There were quite a few of them:

Among the many resorts of the USSR, it is hard to find one without a sanatorium of the Party Central Committee or the government — either union-level or republican. And even if fate, or the whim of a department head, sent him to a very small resort, like my native town of Berdyansk on the Sea of Azov, he would not have to humble himself and stay in a sanatorium together with ordinary people: even there he would find a Party committee dacha where a nomenklatura vacationer could stay. By contrast, no amount of money would allow an ordinary Soviet citizen to get into such sanatoriums or such dachas9.

Food

Nomenklatura members had coupons for so-called “therapeutic meals” — known as the «Kremlёвka». Three coupons were issued per day (for breakfast, lunch, and dinner). Voslensky writes: “The ration consisted of a set of top-quality products that could not be found in any Moscow store. It was distributed at the Kremlin cafeteria on 2 Granovsky Street, as well as in the House of Government, in the closed distributor at 2 Serafimovich Street10”.

American journalist Hedrick Smith in his book «The Russians» described a scene where nomenklatura officials and their wives hurriedly emerged from a shabby door with a glass sign reading “Pass Bureau”, carrying plump bundles wrapped in brown paper, and climbed into their waiting limousines11.

Still, even without the «Kremlёвka», Soviet officials did not go hungry:

When you visit a nomenklatura official at home, you are always struck by the variety and excellent quality of the food served. In nomenklatura institutions — whether in Moscow or in the provinces — excellent cafeterias and buffets are a constant attribute, and eating there is a pleasant ritual in a nomenklatura life.

At the CPSU Central Committee, special buffets opened at 11 a.m. They quickly filled with imposing nomenklatura figures, who never failed to stop by for a second breakfast. All the products in the buffets were of the highest grade, impeccably fresh, and sold at low prices. True, the portions were comparatively small, but this was not due to stinginess (would the nomenklatura be begrudged?), rather so that the breakfast would be light and officials would not grow fat. On small plates lay servings of grainy and keta caviar, on platters excellent fish of various kinds: salmon, beluga flank, sturgeon. There was always the famous drink of the eastern steppes — kumis (fermented mare’s milk). The soured milk there was so thick it was hard to tell it from sour cream. The cottage cheese with sugar smelled fresh and melted in your mouth. In short, everything there was of the very best — the kind of things an ordinary Soviet consumer could not even dream of12.

By the Perestroika era (which is why we know such details), the cafeteria of the Leningrad City Committee of the CPSU in Smolny received annually 300 kilograms of salmon caviar and 550 kilograms of sturgeon caviar, as well as 204 tons of sausages — almost a ton for each working day. In addition, the staff of the City and Regional Committees of the CPSU, the city and regional executive committees, and the KGB of Leningrad annually received in their cafeterias over 156,000 cans of preserved foods and about 150 tons of smoked meats13.

Public Consumption Funds

The nomenklatura received for free (that is, at the expense of other citizens) a wide range of services and goods — something that continues to this day, it should be noted — so that they did not have to be distracted by everyday problems and could devote all their free time to searching for enemies abroad and at home, while bolstering patriotic slogans:

If Stalin’s “packets” were a secret part of the nomenklatura’s salary, then the benefits we will discuss here can well be attributed to the category known in Soviet economic literature as the “invisible part of wages”.

The term was used for a long time and was later replaced by the expression “public consumption funds”. This referred to free and subsidized vouchers for sanatoriums and holiday resorts, the allocation of apartments, sending children to nurseries, kindergartens, and Pioneer camps, as well as cafeterias, hospitals, and clinics. The share of the average worker or employee in receiving all these benefits was calculated by Goskomstat of the USSR, naively assuming that they were distributed equally among everyone, with preference given to the least well-off. As a result, the “statistical worker” supposedly received places in sanatoriums of the Central Committee, the Council of Ministers, and the KGB, and even some space in state dachas. However, the real worker in the USSR knew full well that he was never allowed anywhere near such benefits. That is why the terminology was changed: someone in the leadership finally reflected on the words “invisible part of wages” and detected the irony in them14.

Alexander Kirpichnikov in his work «Russian Corruption» also confirms the fact that most of these instruments are still used by today’s nomenklatura:

Hidden privileges of the nomenklatura contradict the Constitution, but, following Soviet tradition, they are given the appearance of legality through classified normative acts, or else implemented through special supply chains. In Soviet times, cafeterias and shops serving the nomenklatura sold goods at preferential prices, and entry to these establishments by special passes was allowed only for the officials themselves or their family members. Today this tradition continues in the cafeterias of the State Duma, the Federation Council, the White House, and the Kremlin. Prosecutors and judges, along with their wives and children, receive free medical care and free medicines. Employees of the Prosecutor’s Office are entitled to severance pay depending on their years of service: with 20 years of service, this amounts to 20 months’ salary. Deputies of the State Duma, when going on vacation, receive a health allowance equal to double their salary. Both deputies and judges, as well as prosecutors and military personnel, enjoy the right to free travel to their vacation destination and back, along with additional days off for travel. All of them also receive discounts on utility payments15.

Taxation

In many social-democratic countries, for example in Scandinavia, there is a progressive tax system, which helps shift the tax burden from the poorer layers of society onto the wealthier, thereby reducing social inequality. How was it in the USSR? Let us read Voslensky:

Income tax, before the price reform of April 1991, was already levied starting from a monthly salary of 101 rubles — just slightly above the official poverty line. After that, the tax rate rose steeply — fiftyfold — but only when it came to low earnings (up to 150 rubles per month). At 150 rubles, however, the progression suddenly stopped. A tax of 13% was taken both from a modest salary of 150 rubles and from an excellent salary of 700 rubles per month. That was the salary of a regional party secretary or our own Central Committee sector head. In other words, the halt in progression covered the core of the nomenklatura16.

Thus, in social-democratic countries — which nomenklatura propagandists condemned as “petty-bourgeois” — the burden on the rich was far more significant than in the “proletarian” USSR.

Foreign travel

It is no secret that for ordinary citizens traveling abroad was extremely difficult. The right to receive permission for foreign business trips was comparatively easy to obtain only for members of the nomenklatura.

Every business trip abroad, even for a short time, was extremely profitable. Just watch how tirelessly Soviet diplomats, journalists, specialists, and their wives run through shops in Western countries, how strictly they save precious hard currency in order to buy as many things as possible. Given the chronic shortage of consumer goods in the USSR and other socialist countries, foreign goods were not only necessities and prestige items, they were capital: they could be resold at a great profit. Nomenklatura officials — of course, not personally, but through some friend of their wife’s aunt — often sold abroad-bought items that suddenly turned out to be “unnecessary”, “the wrong size”, or “fallen out of favor”17.

Tourist trips were mainly taken by people from trade unions, city party committees, store directors, warehouse managers, and other individuals who were “entitled” to them. And then these same people would tell stories about the “decaying West” — a place they themselves gladly visited while denying access to others.

Currency exchange rates

During those same trips abroad, the nomenklatura enjoyed a separate exchange rate, far more favorable than that available to ordinary citizens:

The government newspaper «Izvestia» publishes a bulletin of foreign exchange rates — from the point of view of an ordinary Soviet citizen unfamiliar with the intricacies of international settlements, a ridiculous table of figures, consisting, for some reason, of three parts: the “official” rate, the “commercial” rate, and the “special” rate, according to which the ruble is respectively three times and ten times cheaper. Foreigners and Soviet citizens traveling on private trips abroad may exchange currency at these rates. For officials, the official rate applies.

What does this actually mean? Only that nomenklatura members on official trips received their currency calculated at the favorable “official” rate. Citizens traveling abroad privately, however, had to exchange money at the extortionate special rate — receiving ten times less for each ruble than officials on assignment, since their trip was not official!

The very operation of having three exchange rates is astonishing. In what other country does the state openly cheat, giving its own currency three different values, with one ten times higher than another?18

Apartments

In the USSR, as is well known, apartments were provided free of charge by the state — except they did not always go to people without high rank. Typically, such apartments, bypassing those on the waiting list, were taken by some nomenklatura member with influence over distribution. Voslensky recalls:

At the Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the USSR Academy of Sciences, the long-promised allocation of housing for those on the waiting list was expected — of course, not for all, but for one or two people. Such an event did not occur every year, so the local committee (I was then deputy chairman) once again carefully clarified the list of those most in need of housing. At the top of the list was a young research associate who had no housing at all and was renting a corner somewhere, and another whose family had only 3 square meters per person. And suddenly it turned out that the housing had already been allocated to the institute: instead of the waiting list, a new apartment went to the institute’s first deputy director, who had previously been secretary of the party committee. Because of this, he declined the cooperative apartment he had been offered (for which payment was required) and took the free one. The apartment was large, so the housing quota allocated to the institute was exhausted for a long time. The deputy director, moreover, had no intention of using the newly acquired apartment in the coming years, since he was leaving to work at the UN. Later he became the Soviet ambassador to one of the African countries. I will not name him: he was no monster, but rather an ordinary, even likable nomenklatura member. But such were the customs of this class19.

This case was not an exception, but the rule, as calculations from official statistics showed:

In 1989, according to the report of the USSR State Statistics Committee, “the housing provision for the population had already reached not 14.6, but 15.8 square meters of total space”, including 10.6 square meters of living space per person… This would mean that the average Soviet family — husband, wife, two children, plus a grandmother — had an apartment of 79 square meters, including 53 square meters of living space and 26 square meters of auxiliary space. In practical terms, this would amount to roughly the following: a five-room apartment consisting of a parents’ bedroom of 15 square meters, three rooms of 9 square meters each for the children and the grandmother, a living room of 11 square meters, a dining room-kitchen of 12 square meters, a bathroom of 6 square meters, and a hallway of 8 square meters. Not bad, is it?

But this optimistic picture is spoiled by the same Goskomstat report. It turns out that among families living in Soviet cities, “every fifth is on a waiting list to receive housing (a third of them have been waiting from 5 to 10 years, and 18 percent for more than 10 years)”. But wait a moment: you are only placed on the waiting list if your family has no more than 5 square meters per person! This means that 20% of urban families were short of 5.6 square meters per person and, for a significant portion of their lives, could not obtain the housing space legally due to them.

Who fattened themselves at the expense of many millions of urban dwellers? Was it really the rural population? But there weren’t that many of them: of the 139 million employed in the USSR’s national economy, only 11.6 million were collective farmers, that is, 8.3%.

No, it wasn’t the rural population who built themselves palaces at the expense of the square meters denied to city residents, but other city dwellers. And not the much-maligned “black marketeers” or co-op members, who were blamed for everything, but first and foremost the nomenklatura. Take a look at their apartments, admire their dachas, and you will see for yourself.

This means that for ordinary people in the Soviet Union, the actual average living space was even less than 10.6 square meters per person. For the spacious nomenklatura apartments, mansions, and state-owned dachas were obtained at the cost of the housing of ordinary Soviet citizens. Think about it, reader: many millions of people in the USSR lived and died in dreadful overcrowding because the nomenklatura had stolen the modest living space that was rightfully theirs!20

Soviet officials usually did not settle for small apartments. Housing for them was built in separate, almost aristocratic quarters, and the number of rooms could reach as many as eight. If the tenant held an especially important post, he might be given an entire floor, created by joining two apartments on the same landing21.

A special construction and installation department built housing for the nomenklatura. These were not the standardized, rushed housing blocks that began to appear under Khrushchev and were popularly dubbed “khrushchoby” (a pun on Khrushchev and “slums”). These were solid and elegant buildings with softly gliding, noiseless elevators, comfortable staircases, and spacious apartments. If you, reader, ever go to Moscow, take a look at the complexes of these houses on Kutuzovsky Prospekt, in the Kuntsevo district, or in Novye Cheryomushki. Such buildings also stand alone, embedded among other houses in the central yet quiet lanes of the capital: for example, the famous building on Granovsky Street opposite the Kremlin canteen, or the house on Stanislavsky Street. Take a look at the building for the top KGB officials on Malaya Gruzinskaya, the house for trade representatives and heads of foreign trade organizations near the Fili metro station, or the hotel for Warsaw Pact generals in the Universitetsky Prospekt area. And if you don’t go to Moscow but instead visit East Berlin, you will easily find there a whole district known, as they say, as der Wolgadeutschen — in the sense that the Germans who lived there had official Volga cars. After the 1989 revolution in the GDR, one could also see the villas of top officials in the suburban residence settlement of Wandlitz22.

The more prominent a nomenklatura member was, the more carefully he had to disguise himself and conceal his life from the people. For example, Leonid Brezhnev was officially registered as living in a five-room apartment in a large, not very new building on Kutuzovsky Prospekt, 26. A policeman in uniform stood guard there, along with a no-parking sign, and ordinary Soviet citizens admired such apparent simplicity. But in fact, Brezhnev never lived there — the apartment was merely registered in his name.

Of course, Brezhnev also had an apartment in Moscow — on the same side of the same Kutuzovsky Prospekt, in a new building at No. 42–44. The security there was more than just a single policeman, and the apartment was not a five-room flat but a duplex connected by an internal staircase and elevator. Yet Brezhnev himself, like other members of the ruling nomenklatura elite, lived at a dacha outside Moscow, near the village of Usovo, while the apartment served him much like the “Kremlin guardhouse” once did for Stalin. Incidentally, the Usovo dacha itself had belonged to Stalin; it was known as the “Farther Dacha”, in contrast to the “Nearer” one at Kuntsevo where Stalin died. The “Farther Dacha” was later occupied by Khrushchev, and photographs of this two-story white palace with columns and balconies, with dozens of rooms, were published in the Western press during Khrushchev’s time23.

Country Houses

A country house, or, as it was commonly called at the time, a “dacha”, could be built by obtaining a plot of land from the district executive committee for dacha construction or by purchasing it from an owner with the same committee’s permission. However, such permits were usually issued only to persons holding appropriate positions. Purchases could be made only with “earned income”: since a good dacha near Moscow cost around 50,000 rubles or more, the district executive committee would never issue a permit to an ordinary worker for whom that sum amounted to 28 years of salary24. And what about the dachas of the nomenklatura?

Our sector head is provided with a dacha virtually free of charge. Without spending thousands of rubles (which, unlike the ordinary worker, he has), without searching for the of-course scarce construction materials, and without the trouble of building or later repairing the dacha, the sector head simply arrives at a fully finished home. A government dacha is allocated to him and his family for the entire summer season in a conveniently located settlement surrounded by a high fence. The settlement has an excellent grocery store, a very good canteen, a cinema, a club, a library, and a sports ground. The rent for the dacha is purely symbolic. A good highway leads directly to the settlement, along which the sector head, in his official car — a black Volga with a Central Committee plate — drives straight from Staraya Ploshchad.

In winter he leaves every Friday after work for a Central Committee guest house. There he, his family, and even his guests are given an entire apartment. They enjoy excellent meals — again at very low cost — use skis and skates free of charge, and watch movies in the evenings.

Although the sector head usually occupies the same dacha year after year, he always remembers that the dacha is not his. This does not mean he treats it with special care (quite the opposite!), but rather that he does nothing at all to improve it. These dachas make a strange impression: around the houses you will not find a single flower, everything is confined to a flowerbed planted by workers; no one hammers in a nail to secure a board (the dachas, as always in Russia, are wooden); even the smallest repair need is reported to the settlement administration. The nomenklatura lie in hammocks, stroll, play tennis and volleyball, eat and drink on the terrace, and go to the cinema. The contrast with ordinary dachas, where half-naked, disheveled owners spend the whole day digging, repairing, watering, is striking25.

Dachas were also acquired for private use, but never in one’s own name: they were registered under parents’ names, while cars could be registered under the names of adult children or a brother.

During Perestroika, information about generals’ “dachas” began to leak into the Soviet press. In the settlements of Dachnaya Polyana, Barvikha, and Gorki-6, palaces were built for marshals and high-ranking generals. By 1990, there were more than 70 such dachas in the Moscow region. One of them, the so-called “Object No. 10”, was built for the Chief Inspector of the USSR Ministry of Defense: 341 square meters, 9 rooms, marble and granite. The plot exceeded 2 hectares and included a pond. The expenses for this dacha amounted to 343,000 rubles.

The marshals’ palaces were more spacious than those of the generals, and their plots were larger. Marshal Akhromeyev lived in a dacha of over 1,000 square meters, with a plot of 2.6 hectares. His colleague Marshal Sokolov had a dacha of 1,432 square meters on a plot of more than 5 hectares26. For deputy ministers, the dachas were two-story stone houses with a hall, living room, dining room, several bedrooms, a servant’s room, kitchen, bathrooms, and toilets. The plots also included utility buildings, greenhouses, and garages. The budget provided for 350,000 rubles per dacha. But that was not enough: one of the deputy ministers of defense spent 627,000 rubles on his “estate” in Barvikha — naturally, state funds. Such a sum could only have been saved by an ordinary Soviet Army private (whose pay was 7 rubles per month) by the year 9454. Near the dacha of the First Deputy Minister, a reception house was erected. However, not far from this dacha loomed, in the words of a journalist, “a palace three to four times larger and many times more luxurious27”. There lived the retired (!) chairman of the Party Control Commission of the CPSU Central Committee, pensioner Solomentsev.

Marshal and Minister of Defense Yazov, one of the leaders of the GKChP, who today promotes Stalin and the supposed well-being of the common people in the USSR, apparently had in mind himself when speaking of “the people”. His country palace had a usable area of 1,380 square meters, and its “household plot” measured 16.7 hectares28. As Voslensky noted, “This is not a dacha but a latifundium with a rather large palace. According to the housing norm, 100 people should have been living there. But the minister does not pay for the excess living space at fivefold or even threefold rates29”.

But perhaps this was only the case for the military, while officials lived more modestly? Let us turn to the memoirs of Boris Yeltsin, when he became a candidate member of the Politburo and was given a new “dacha”:

When I first drove up to the dacha, the chief of the guard met me at the entrance and introduced me to the staff — cooks, maids, guards, a gardener, and so on. Then the tour began. Even from the outside the dacha was overwhelming in its enormous size. Inside — a hall of about fifty square meters with a fireplace: marble, parquet, carpets, chandeliers, luxurious furniture. We went further. One room, another, a third, a fourth, each with a color television set. On the first floor there was also a huge veranda with a glass ceiling, a cinema hall with a billiard table. I lost count of the number of bathrooms and toilets. The dining room had an incredible table ten meters long, behind it the kitchen — practically a catering complex with an underground refrigerator. We went up the wide staircase to the second floor. Again a huge hall with a fireplace, from it an exit to a solarium with deckchairs and rocking chairs. Then a study, a bedroom, two more rooms with no clear purpose, again bathrooms, toilets. And everywhere crystal, antique and modern chandeliers, carpets, oak parquet, and so on30.

Pavel Sudoplatov recalled it without many details:

Abakumov showed enough tact not to deprive me of the privileges I had enjoyed during the war years: I retained my government dacha, I continued to be included on the list of people who, in addition to their official salary, received monthly monetary rewards, and I also retained the right to special services and meals in the Kremlin canteen31.

Strict rules of security and secrecy were observed:

The government dachas near Moscow are located in restricted areas, their surrounding parks fenced off by towering walls and heavily guarded. The leaders of the nomenklatura, forever proclaiming their closeness to the people, fenced themselves off from them more thoroughly than any feudal sheikh32.

The government dachas near Moscow were even sung about by Alexander Galich:

Perhaps this happened only in the Soviet Union? In other countries with a planned economy and a nomenklatura, was there no such arbitrariness?

In the summer of 1970 I spent a few days living like this in Sofia, together with the First Vice-President of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR M. D. Millionshchikov, and Academy Vice-President A. P. Vinogradov. We were accommodated in a government mansion that had once belonged to the sister of Tsar Boris, and later to one of the communist leaders of Bulgaria — Vasil Kolarov. The mansion was on a quiet street not far from the city center. As expected: a fence, iron gates, a guard at the entrance, and a large shady garden behind the house. To the right of the entrance stood two black “Chaikas” with government plates and polite, solid-looking chauffeurs. The house had service staff, but we dealt only with one — apparently the head servant. Any dish, wine, or cognac could be ordered from him, and everything appeared immediately33.

Cars

The upper echelons of the nomenklatura usually rode in ZIL limousines (equipped with English-made air conditioners and other equipment from Rolls-Royce factories), while lower-ranking officials rode in black Volgas with special license plates. For example, Central Committee plates often began with the letters “MOS”, and a popular saying went: “Don’t stick your nose in a MOS car!34”.

However, if a department head went to meet an important foreign delegation (less important ones were met by a secretary or instructor), he would be sent a “Chaika” — a big black car gleaming with lacquer and chrome. These were officially intended for Deputy Chairmen of the USSR Council of Ministers, but in practice they were provided to virtually any top-level nomenklatura boss, including Raisa Gorbacheva, members of Ryzhkov’s family, and so on35

The first postwar Soviet car was the ZIS-110 limousine, which went into mass production as early as 1945. The nomenklatura was eager to reward itself for victory in the war as quickly as possible — the development of a representative automobile was fast-tracked, while workers and peasants still had to make do with the ration-card system for basic necessities.

The cars were also provided with special security measures:

The nomenklatura leaders rode in Stalin-style — in armored ZIL cars equipped with radiotelephones, green-tinted bulletproof glass, and, of course, accompanied by plainclothes security guards. For security reasons, license plates were changed almost daily. Family members were served by Chaika or Volga cars… The cars of the bosses and their guards were refueled with high-octane gasoline at special KGB gas stations36.

Servants

Despite the fact that Marxism condemned the use of hired labor (during collectivization, this could get one branded as a “kulak”, with all the corresponding consequences), this did not prevent Joseph Stalin and his inner circle from maintaining a large staff of servants (there is plenty of information online about Stalin’s housekeeper Valentina Istomina, his chief of security Nikolai Vlasik, his physician Vladimir Vinogradov, and even Vladimir Putin admitted that his grandfather had been a cook for the General Secretary37). Later, the nomenklatura did not give up such conveniences either. In fact, Bolsheviks had hired workers almost immediately after coming to power — even Vladimir Lenin had them.

Nomenklatura members with personal cars also had personal chauffeurs. A chauffeur was part of the service staff, which in nomenklatura circles was haughtily referred to as the “servants”. This included housemaids, nannies, tutors for schoolchildren, and, of course, secretaries. The latter was an influential figure, a trusted confidant of the nomenklatura official.

But perhaps an even more trusted figure was the chauffeur. Unlike the secretary, he knew exactly where his boss was going — both for official business and strictly personal matters — he knew his boss’s friends and all his connections. The official understood this. The cautious B. N. Ponomaryov, later a Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and a candidate member of the Politburo, when still head of the Soviet Information Bureau, would drive his official Pontiac to the Kremlin, the Central Committee, the Council of Ministers, etc. For personal trips, however, he would call a taxi. But usually nomenklatura officials chose another path: they granted their chauffeurs all sorts of indulgences, thereby creating a community of shared interests38.

The subject of chauffeurs was also featured in the 2004 film «A Driver for Vera». But even in Soviet times it was no secret — for instance, in the 1956 film «Different Fortunes», there is a scene depicting a conversation between two nomenklatura drivers, one of whom is played by the famous actor Sergei Filippov:

From an anonymous letter to the newspaper «Socialist Industry», 1986:

We are tied to our bosses with the same rope. We are the personal chauffeurs of nomenklatura bosses. We are allowed everything, and you know perfectly well why. For us, there are no problems at all. Gasoline? They’ll write off as many liters as needed… We also shop for scarce goods from bases and special buffets, and we get medical treatment in special clinics and hospitals — in short, we’re well taken care of… All the overtime we rack up with them on hunting trips, fishing, at bathhouses, or on other private matters is generously paid… We and our bosses were, are, and will be together: with no limits and with access to scarce goods. How could it be otherwise? Our bosses are reliable people39.

If a mid-level nomenklatura member could manage with just one cook, it was impossible to feed higher-ranking officials with such a small staff:

Even a candidate member of the Politburo is entitled to staff: three cooks, three waitresses, a maid, and a gardener, as well as, of course, bodyguards. If the boss goes to the cinema, the theater, a museum, etc., a KGB team is first dispatched there to check and ensure security. Bodyguards even accompany their charge on vacation40.

Since the time of Stalin, the Ninth Directorate of the KGB of the USSR was responsible for the security of the nomenklatura elite. As Boris Yeltsin recalled, the head of his personal security detail would bring about 4,000 rubles to his vacation spot — for Yeltsin’s personal expenses during the holiday. As a result, Yeltsin did not spend anything from his rather considerable salary while on vacation41.

Special Stores

It is well known that under the planned economy of the USSR there was almost always a shortage of consumer goods (we wrote about this in the article on the standard of living in the USSR). So, did the nomenklatura also face this problem? Not at all. The Soviet Union had a network of special stores, buffets, and sections — Svetlana Alliluyeva recalled the “better and cheaper stores42” to which she was graciously granted access.

The Moscow telephone directory listed Branches No. 1 and No. 2 of Store “Beryozka” No. 4 (12/5a 1812 Goda Street, and Rostovskaya Embankment), marked with the note: “Not open to the public”. So who then? The privileged.

You are privileged and have come to such a special store. The doorman at the entrance gives you a scrutinizing look: are you part of the “contingent” or just an insolent Soviet citizen who must be put in his place and told not to sit in someone else’s sleigh? If you are well-dressed, look respectable, wear foreign items, and ignore him, he will let you through. Otherwise, he will ask where you are going and tell you to leave. And you will leave silently, because you know: otherwise, there will be trouble. You, the Soviet citizen, have been shown your place43.

In 1968, Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote the poem «Russian Miracle» about an old woman who wandered into such a foreign-currency store and imagined that she could buy groceries there with Soviet money:

…but then a guard appeared, full of might:

“Do you have certificates?” — he asked outright.

She didn’t understand: “What, my son?”

And he showed her the door, job well done.

He knew in security there was no lack,

the pass to communism was a certificate pack.

And without the slightest reproach at all,

in Moscow’s frosty, snowy sprawl,

Aunt Glasha left communism’s door

stooped, with an empty shopping bag, once more.

Most of the archives related to the Beryozka special stores remain classified to this day. In 2015, the Ministry of Finance proposed reviving this network of special shops44.

Special children

The nomenklatura made sure that their children did not study in the same institutions as the children of the common rabble. Whenever possible, they were placed in separate schools.

The desire to separate the offspring of the nomenklatura from ordinary children manifested itself at the moment when Stalin’s nomenklatura rose to the heights of power in the late 1930s, when special schools were suddenly created. Officially, they were intended to train future young commanders of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, as the Soviet Army was then called. In reality, they were privileged schools that primarily admitted sons from high-ranking, decidedly non-working-class families. My classmate Rafik Vannikov, son of the Deputy People’s Commissar of the defense industry, whom I have already mentioned, was immediately transferred to such a school. Girls from noble families began to be concentrated in several so-called “exemplary schools”, which were hard to get into. Nowadays, nomenklatura children are placed in special schools with instruction in foreign languages (English, French, or German), while the children of diplomats and other officials working abroad attend special boarding schools.

And when it comes time to enter university, the children of worthy parents need not mix with the crowd of ordinary students but may remain within their own circle. For this, the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) exists.

Visit it — and you will at once sense the cultivated, arrogant, caste-like spirit, similar perhaps to that of the Tsarist Page Corps. There are a number of closed educational institutions — the Higher Party School of the CPSU Central Committee, the Diplomatic Academy, the Academy of Foreign Trade, military academies, and the higher schools of the KGB and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Most of these institutions admit only those who have already graduated from university and have experience in responsible Party work. Thus, the transition of nomenklatura children to occupying nomenklatura positions of their own takes place smoothly45.

In 1931, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) issued a resolution “On Primary and Secondary Schools”46, which, among other things, called for the creation of a network of exemplary schools. Stalin’s son and daughter studied at the 25th Exemplary School on Pimenovsky Lane. The children at this school were being prepared to become masters of the country and to seize the whole world; one of them even created a secret organization called the “Fourth Reich”, in which the sons of Anastas Mikoyan were implicated. This episode is described in fictionalized form in Alexei Kirpichnikov’s novella «Stalinjugend».

Special Country

In fact, communism in the USSR was already built — but only for the nomenklatura. They lived as if in a separate country, able to take “according to their needs”. But this arrangement was ensured only by erecting barriers between themselves and the working people. As a result, the notorious Russian rudeness in mass services was born — there was simply no one to suppress it. For example, a sales clerk in an ordinary store knew that he was facing a powerless citizen who could not put him in his place, and so could behave rudely with impunity. In the nomenklatura’s special country, however, such things did not happen.

Ordinary Soviet citizens were walled off from this special country as thoroughly as from any foreign land. And in this country, which could be called “Nomenklaturia”, everything was special: special residential buildings constructed by special construction administrations; special dachas and guest houses; special sanatoriums, hospitals, and clinics; special food products sold in special shops; special canteens, buffets, and hairdressers; special motor pools, gas stations, and license plates; a ramified system of special information; a special telephone network; special children’s institutions, special schools and boarding schools; special higher educational institutions and graduate schools; special clubs showing exclusive films; special waiting rooms at railway stations and airports — and even a special cemetery.

A nomenklatura family in the USSR could pass through life from cradle to grave — to work, live, rest, eat, shop, travel, be entertained, study, and receive medical care — without ever coming into contact with the Soviet people, whom the nomenklatura was supposedly serving. The separation of the nomenklatura class from the mass of Soviet citizens was the same as the separation of foreigners residing in the Soviet Union: the only difference was that foreigners were not allowed to mingle, while the nomenklatura did not want to mingle with the Soviet population47.

In many ways, this closed nature is the reason why we still have so little data and so few sources on the privileges of the nomenklatura.

Treatment

Important officials were served by the Fourth Main Directorate of the USSR Ministry of Health, also known as the Kremlin Medical Directorate or the “Medical and Health Association under the Council of Ministers of the USSR”. A Moscow nomenklatura member and his family were assigned to the Kremlin hospital and clinic, where they had a permanent attending physician. And what was this clinic like?

It was a luxuriously equipped medical complex spread across several buildings. New branches of the Kremlin hospital kept being opened: a huge 2,000-bed health center for Party apparatus employees on the Lenin Hills, a new building in a forested area at the end of Otkrytoye Highway, another new building at the Central Committee sanatorium on Stalin’s “Near Dacha”. But the doctors there were mockingly described as: “Parquet floors, questionnaire doctors”. Indeed, the physicians were selected according to the notorious “political qualities”, but in fact they did not treat patients themselves: in any somewhat serious case they referred the sick nomenklatura member to a consultant. And the consultants were the most prominent Soviet medical scientists, members of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences. The best among them served as personal physicians to the ruling elite of the nomenklatura class. When Stalin fabricated the “Doctors’ Plot”, the entire flower of Soviet medicine ended up in the underground prison of the Lubyanka, because they were the very ones treating Politburo members. The old dictator did not trust the knowledge of the “questionnaire doctors”, and when he fell ill in the midst of the “Doctors’ Plot”, he was left without medical help and died of a stroke, while his personal physician, Professor Vinogradov, beaten nearly to death and chained up on Stalin’s orders, lay in the basement of the Lubyanka.

The intimidated Kremlin doctors tried to treat their fearsome patients, whenever possible, by holding a medical council, so that no single one of them would bear responsibility for the results of treatment.

In ordinary hospitals, corridors were crammed with beds, there was a shortage of medical staff, and the food was so poor that it was impossible to survive without packages from relatives. In the Kremlin hospital, by contrast, equipment and medicines were imported from abroad (for such an essential matter as their own treatment, the nomenklatura did not rely on domestic technology or pharmacology). Patient care and nutrition were excellent, staff plentiful, and rooms private.

And higher-ranking nomenklatura members received special rooms — “lux” and “semi-lux”. The “semi-lux” was described by a Soviet writer as follows: “…The semi-lux contained a study and a bedroom, a balcony, a bathroom, and an entrance hall with direct access to a staircase carpeted with a runner. In this bright, spacious abode… there were soft armchairs, carpets, expensive statuettes, and heavy gilded frames of paintings hanging on the walls48”.

And the “lux” was briefly described by former candidate member of the Politburo B. N. Yeltsin: the most modern medical equipment, all imported. The hospital “ward” was in fact a huge apartment, with luxury everywhere: dishes, crystal, carpets, chandeliers…49

An ordinary Soviet worker would end up in a district hospital only when his condition was already critical. But in the shining halls of the Kremlin hospital, nomenklatura officials and their family members often checked in simply to rest.

For convalescents and chronically ill nomenklatura members, there was also a suburban branch of the Kremlin hospital, located in the Kuntsevo forest park50.

Tickets

For the best events in the USSR – important sports matches, concerts, theater performances – there existed a “government reservation”. Ordinary people were not entitled to occupy the best seats.

Getting theater tickets for a nomenklatura official was very easy: there was a government reservation for the best seats. However, being known as a theater-goer in nomenklatura circles was not recommended: it was considered frivolous or indicative of some questionable tastes and inclinations. Therefore, these ticket privileges were usually used by older nomenklatura children, as well as relatives and acquaintances who had not quite reached the nomenklatura status51.

Of course, this applied not only to leisure events but to tickets in general:

On all airplanes, trains, and in hotels, a certain number of seats were always reserved in case the “authorities” wished to use them. For an ordinary Soviet person, this was a familiar part of daily life: they knew there was a so-called “government reservation” for the best seats, and these seats were not released for sale to ordinary citizens until half an hour before the departure of a train, ship, or airplane. In hotels, some of the reserved rooms were not occupied at all, since the hotel was stationary and nomenklatura members could appear at any time. The transport service sector of the CPSU Central Committee was one of the main places where the nomenklatura obtained tickets for reserved seats.

A Western reader should understand that in the USSR, trains and airplanes were always overcrowded. Only in the West did I first see that one could calmly go to a ticket office at a station and buy a ticket. In the Soviet Union, enormous lines stood for entire days even at advance ticket offices, not to mention the station itself, so ticket reservations were a very pleasant privilege of the nomenklatura class52.

Where there is ticket reservation, which is not always used, there is also ticket speculation. As a result, the theater loses revenue, the honest visitor misses out on good seats (instead facing higher prices for the remaining tickets), and only the nomenklatura and those feeding off them benefit.

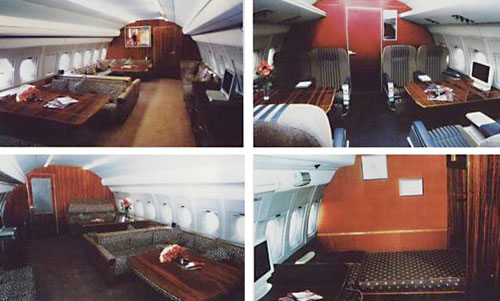

Airplanes

Nomenklatura members rarely flew with other passengers, not wishing to see the common people unnecessarily. For them, either separate sections of the airplane or entire aircraft were provided.

Soviet ministers flew on scheduled flights, occupying the entire first-class section alone. The door between first and second class was securely locked. Higher-ranking officials used special airplanes. Members and candidate members of the Politburo, as well as CPSU Central Committee secretaries, flew on excellent IL-62 and TU-134 airplanes accompanied by their security; no one else, except the flight crew, was allowed on board. A special airport, Vnukovo-2, was dedicated to servicing this handful of passengers.

The airplanes were very comfortably equipped: a flying apartment – with a lounge, office, bedroom, and kitchen. I once flew on such a plane belonging not to one of the top nomenklatura leaders, but merely to a Marshal of the Soviet Union, and I can say that the airplane was very convenient.

And there, the vehicles were even better and more spacious: they regularly transported a single passenger. He would solemnly arrive in his black limousine directly at the airplane, ascend the ramp with his security, and the car would depart. This was not for any special official occasions, but simply when he flew for a few days of rest or hunting. Members of high-ranking nomenklatura families also traveled this way. Afterwards, an empty plane was sent to transport them along with their security back to Moscow.

Here is an example: on February 13, 1990, Vnukovo-2 airport serviced only three passengers; the Queen of Spain and two un-crowned princes of the nomenklatura, members of the Politburo – Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Medvedev and the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine Ivashko. Meanwhile, the nearby Vnukovo-1 airport handled 106 flights that same day, transporting around 10,000 people.

Could it be that the number of airplanes at these two airports is completely incomparable? Here are the numbers: Vnukovo-1 had 58, Vnukovo-2 had 42 airplanes and 8 helicopters. And at Vnukovo-2, dozens of flight crews and nearly 1,500 ground personnel were employed. It is hardly surprising that, since the early 1950s, the “235th Special Purpose Aviation Squadron” has existed to transport distinguished passengers. At its disposal – its own aviation-technical base. Vnukovo-2 has substantial ground staff: a flight and navigation department, HR department, accounting. All expenses for this luxury are borne by the state; the distinguished passengers do not pay a single kopeck, even when flying for leisure53.

The example of the Soviet nomenklatura proved contagious even for its vassals. In the GDR, following the model of the “235th Squadron”, the “Arthur Pieck Squadron” (named after the son of the communist president of the GDR, Wilhelm Pieck) was created. It had 17 TU-134, TU-154, and IL-62 planes and similarly transported GDR nomenklatura leaders for free5455.

Pensions

When a nomenklatura official leaves office – does it mean they stop extracting state resources and the results of public labor? First of all, such people rarely left office. As Voslensky noted, “A comrade who has entered the nomenklatura can reasonably assume that he is firmly within it. If there are no upheavals or mass purges, if he does not incur the wrath of the highest authorities, if he maintains friendly relations with influential colleagues in the nomenklatura and observes all its written and, most importantly, unwritten rules, then it would take a truly scandalous event for him to be expelled from the nomenklatura56”. Leaving office usually meant retiring. Does that mean they stop relying on society? Not at all:

We mentioned retirement. One might think that, since the person no longer holds a position, their belonging to the nomenklatura automatically ends. Nothing of the sort. Only the designation changes: instead of being called a nomenklatura worker, the comrade is now a personal pensioner of local, republican, or union significance. The purpose of this absurd title is that the personal pension is approved, in the first case, by the bureau of the city, district, or regional party committee; in the second case, by the bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of a union republic; in the third, by the Secretariat or even the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee. This is already a familiar classification scheme of the nomenklatura. The pension turns out not to be personal but nomenklatura-based57.

<…>

The children are grown and have become adults themselves, meaning they have entered the nomenklatura. Years pass, and the department head retires, as is said, with full honors. Unlike ordinary citizens, they do not have to gather numerous certificates and visit the district social security office for a pension, the upper limit of which is 120 rubles per month. The Secretariat of the CPSU Central Committee decides on granting the retiring person a personal pension of union-level significance, and they still live in the Central Committee’s residential building and use its sanatoriums. A military nomenklatura official – a general – lives on an officially assigned dacha: generals are allocated dacha plots, not like ordinary people – 8 sotkas (0.08 hectares), but entire hectares. A colonel-general, and even more so an army general (let alone marshals), is included in the so-called “paradise group” of the USSR Ministry of Defense: they retain all material benefits, a personal car with a driver, an apartment, a dacha, an aide – in short, all privileges, without any work obligations58.

Meanwhile, the incoming generation (usually nomenklatura children) also demands state apartments, dachas, etc. So this is not even inheritance – it is worse.

Special privileges of Central Committee secretaries and Politburo members

The top echelon of the nomenklatura had virtually unlimited possibilities – at their disposal was the economy of the entire country, which they managed without alternative.

How do those mountain eagles of the Nomenklatura, who are buried in Red Square and wave from the Mausoleum, live?

“Like billionaires in America”, a nomenklatura insider once told me in response to this question.

Do not think that they receive a salary of tens of thousands of rubles per month, like CEOs of large Western companies or corporate presidents. Secretaries of the CPSU Central Committee, and even the General Secretary himself, receive salaries in the range of 1,000–1,200 rubles. Of course, this is not the 257 rubles of the average Soviet worker or employee, but it is not fabulously high either. How are they like billionaires then?

The point is that, first, besides their salary and money from deputy positions in the Supreme Soviets, fees, etc., all of them have what is called an open account at the USSR State Bank. This means they can withdraw any sum they need from state funds at any time. Secondly, they do not need any money at all – neither from the open account nor from other payments: they live in luxury on state money without spending a single kopeck of their own. Do not compare the General Secretary to a CEO! A director must use their own – even if large – funds to build and furnish their bungalow, while a secretary only needs to call the Central Committee’s administrative manager via the “rotary phone” and order the preparation of a construction decision for a house or dacha, then sign the decision, and shortly afterward move into a fully furnished and carefully guarded new residence59.

Examples of such residences still exist today – for instance, in central Moscow, the mansion of Lavrentiy Beria on the Garden Ring near Vosstaniya Square (now housing the Tunisian embassy) and the mansion of Georgy Malenkov on Pomerantsev Lane.

Obkom secretaries did not have such wide-ranging opportunities, but within their region, they had almost the same privileges:

The First Secretary of the regional committee was a fully empowered and virtually unchecked satrap in his region, and the other secretaries of the obkom were his closest aides. They not only had high salaries, state apartments and dachas, cars, rations, special hospitals and sanatoriums, but also nearly unlimited access to all the material benefits that their region – roughly the size of an average European country – could provide60.

Immunity

Since in the courts and state security organs a nomenklatura member had “all their own”, no other parties existed, and even the press could not bring an incident to light, they could negotiate any issue where they slightly overstepped the law and not be punished — in some cases, the victim could even be punished instead. Voslensky recalls:

One Western minister, who was simultaneously deputy chairman of the ruling party, while returning from a banquet, hit a neighbor’s parked car with his vehicle. The police confiscated the minister’s driver’s license, and the court ordered him to pay a substantial monetary compensation. In the Soviet Union, it would have been different: the militia would have checked whether the neighbor had bought the car he so brazenly parked there with his labor income61.

Dr. Oleg Khlevnyuk, historian and chief specialist at the State Archive of the Russian Federation, testifies:

Repressions against officials in the postwar period were more the exception than the rule. Moreover, as the documents show, on the eve of Stalin’s death, senior officials enjoyed de facto judicial immunity. Mandatory approval of any sanctions against party members by party committee leadership led to an effective bifurcation of the legal system, about which the USSR General Prosecutor wrote in a report to the CPSU Central Committee shortly before Stalin’s death: “In fact, there are two criminal codes, one for Communists and another for everyone else. There are many examples where, for the same crime, party members remain free while non-party members go to prison”62. The effective separation of justice along class lines resulted from the corporate nomenklatura morality, which tolerated abuses within its own ranks and upheld the law of the strongest63.

Many wonder why Russia has such a low level of rule of law. This is largely due to the nomenklatura’s pursuit of immunity. When people are forced not to pay taxes due to low wages, when they are compelled to break completely idiotic laws (laws that cannot realistically be followed), any citizen can be accused of something if they dare to oppose an official or challenge the authorities. This has been one of the most effective tools to keep the population obedient. The nomenklatura successfully used it and continues to do so to this day.

Other Privileges

Perhaps the most offensive aspect of the nomenklatura’s privileges was that they were inaccessible to ordinary people, even if those people had saved money. Such arbitrariness does not exist even under capitalist free markets. Voslensky even spoke of social apartheid in the USSR:

You are an ordinary Soviet worker living on the periphery or even near Moscow. Try to obtain a Moscow residence permit, in other words – permission to live in Moscow. You will not be granted such a permit, and in the best case, you will end up in the capital in the miserable role of a “limitnik”. Doesn’t this remind you of the South African prohibition against blacks settling in Johannesburg? And this applied not only in Moscow but also in Leningrad and the capitals of the union republics…

Go beyond the city limits, to the dacha area; here there should be space. After long struggles, you obtain a dacha plot – a whole 0.12 hectares. You build a dacha, but it turns out cramped. You save money and add a second floor. Immediately, you are told to demolish it; if you do not comply, it will be torn down without discussion, and you will be found guilty. Who is bothered by your floor? No one. You are simply “not entitled”. Nearby stands a two-story dacha with a plot – complete with a pond and gazebos – the size of a full hectare. Its owner is entitled: he is a general, a nomenklatura official. If you try to request even the smallest plot in the area where higher-ranking nomenklatura dachas are located, not only will it be denied, but the KGB will investigate: are you a spy or saboteur? And even if they find nothing, suspicion remains and will cause you trouble for many years.

Shops, canteens, dachas, educational institutions, residence permits, telephones, hospitals, even cemeteries – some are entitled, others are not. Yes, the difference is not determined by skin color, but there are still “whites” – the nomenklatura – and “blacks” – the rest of the population. This is social apartheid, and it is no better than racial apartheid64.

The privileges of the nomenklatura reached truly frightening extremes. Pavel Sudoplatov, who served under Lavrentiy Beria, recalled:

Abakumov reviewed police documents about Beria’s bodyguards, who would grab women off the streets and bring them to Beria, causing complaints from husbands and parents65.

Actress Evgenia Garkusha, who slapped Beria for his indecent proposition, was soon sentenced to eight years in labor camps on fabricated espionage charges66. Actress Tatyana Okunevskaya recalled being forcibly brought to Beria and given something to drink until she blacked out67, while Beria himself stated during interrogation:

I easily got along with women and had numerous, brief liaisons. These women were brought to my house; I never went to theirs. Sarkisov and Nadaray, especially Sarkisov, delivered them to me. There were cases when, noticing a woman from a car whom I liked, I sent Sarkisov or Nadaray to follow her, establish her address, get acquainted with her, and, if desired, bring her to my house. There were quite a few such cases68.

Regarding other nomenklatura regimes, Mao Zedong’s personal physician, Li Zhisui, wrote in «The Private Life of Chairman Mao» about the “Great Helmsman’s” numerous concubines:

Vice Chairman of the Military Affairs Commission Peng Dehuai twice criticized Mao for love affairs with dancers at Politburo meetings. Peng was one of the most decent and honest members of the Politburo, and perhaps the only one who consistently criticized Mao. Peng stated that Mao behaved like an emperor and maintained about three thousand concubines. He also accused Luo Ruiqing and Wang Dongxing of indulging all the leader’s whims. As a result, the dance troupe was disbanded, but Mao continued to bring young girls to his bed. He mostly found them in dance troupes attached to units of the People’s Liberation Army — in the Beijing Military Region, in the Air Force, in the railway troops, with artillery units, and finally in other provinces — Zhejiang, Jiangxi, and Hebei. The leader did not disdain even female staff of the Central Committee. But in 1955, I did not yet know all this69.

How the Nomenklatura Justified Their Privileges

In the USSR, there was a whole industry of deceiving the population, which had two layers — concealment and justification. The first layer hid all the facts mentioned in this article and many others — the existence of privileges was denied, claimed to be lies by agents bribed by the West, and so on. However, if a person had irrefutable evidence and presented it (often those were nomenklatura members who still had at least some conscience), they encountered the second protective layer of the carefully constructed propaganda system — justification. This was primarily the tales of “the nomenklatura is not a class”, “there is no exploitation in the USSR”, and so on — based on attempts to twist Marxism until it lost its meaning. What good is it to a worker that, according to some dogmatic scheme, they are not exploited, if their machinery, apartment, and food still go to someone else, in this case a nomenklatura member? There were also non-dogmatic justifications, such as the hypocritical lie that privileges were necessary to “maintain the prestige of the country and socialism”:

As for representative purposes, the nomenklatura indeed uses them to justify the luxury of apartments: any nomenklatura member will publicly claim that nothing is more desirable to them than living in the simplicity bequeathed by Lenin, but their representative duties compel them to live in luxury so as not to undermine the authority of the Soviet state. However, this is an argument for outsiders. Within their own circle, nomenklatura members openly admire their apartments, furniture, and paintings. And which nomenklatura officials receive foreigners at home? Occasionally, perhaps some deputy foreign minister — for example, the long-serving Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, later USSR Ambassador to Bonn, V.S. Semyonov, in his Moscow apartment, arranged like a museum. Otherwise, all this talk about representation is just that — talk70.

Also, the matter was heavily influenced by the demagogic techniques described in this article.

Conclusion

Every time nomenklatura members and their propagandists praise Joseph Stalin and the system created under him, or cultivate nostalgia for the USSR, it is hard to believe them — especially when one knows the luxury they indulged in at that time and how they oppressed anyone who dared to challenge the nomenklatura. Their goal is to bring back that era. Our goal is not to believe them or the propagandists of big business, but to build a society based on social justice that serves the interests of the majority of citizens. Incidentally, propagandists came up with the “justification” that all the privileges described above in the USSR were not inherited. We examine this manipulative attempt in a special report.

While reading this article, you have likely noticed how similar all this is to modern United Russia members and officials. It is not surprising — the nomenklatura in the early 1990s simply changed the economic course, and slightly the political one, but the people remained the same. And without lustration of the nomenklatura, the aforementioned privileges will continue to exist and multiply.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (Second, revised and enlarged edition), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd, London, 1990. — pp. 124–125.

- «Pravda», 13.02.1986

- «Pravda», 13.02.1986

- CPSU. Congress (27; 1986; Moscow). «27th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, February 25 – March 6, 1986: Stenographic Report». [In 3 vols.]. Vol. 1. — 654 p. — Moscow: Politizdat, 1986. — p. 402

- «Arguments and Facts», 1989, No. 25

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (Second, revised and enlarged edition), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd, London, 1990. — p. 295.

- Ibid., p. 296.

- Ibid., p. 293.

- Ibid., p. 344.

- Ibid., p. 293.

- Hedrick Smith. «The Russians». New York: Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., 1976, p. 43.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (Second, revised and enlarged edition), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd, London, 1990. — p. 310.

- «Izvestia», 18.09.1990

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (Second, revised and enlarged edition), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 296.

- Alexander Kirpichnikov – «Russian Corruption»

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class», Moscow, 1991

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (Second, revised and enlarged edition), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 297.

- Ibid., p. 298.

- Ibid., p. 322.

- Ibid., pp. 323–324.

- Ibid., p. 320.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., pp. 358–359.

- M.S. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Ruling Class of the Soviet Union». – 624 p. – Moscow: “Soviet Russia” in cooperation with MP “Oktyabr”, 1991. – p. 304.

- Ibid., pp. 325–326.

- «Ogonyok», No. 21, 1990

- «Ogonyok», No. 13, 1990; «Sovetskaya Kultura», March 31, 1990

- «Ogonyok», No. 21, 1990

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 368.

- B.N. Yeltsin. «Confession on a Given Theme». – 240 p. – Sverdlovsk: Middle-Ural Book Publishing House, 1990. – p. 151.

- Pavel Sudoplatov. «Razvedka i Kreml. Zapiski nezhelatel’nogo svidetelya» [Intelligence and the Kremlin: Notes of an Unwanted Witness]. — 508 p. — Moscow: TOO “Geya”, 1996. — p. 286.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 359.

- Ibid., p. 373.

- Alexey Bogomolov – «Leaders of the USSR in the Revelations of Comrades, Guards, and Staff»

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 327–328.

- Ibid., p. 369.

- Putin revealed that his grandfather worked as a cook for Lenin and Stalin // TASS (tass.ru). March 11, 2018, 16:17. [Online resource]. URL: https://tass.ru/obschestvo/5020931 (accessed: 29.11.2019).

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 328–329.

- «Socialist Industry», December 7, 1986.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 371.

- B. N. Yeltsin. «Confession on a Given Theme». — 240 p. — Sverdlovsk: Sred.-Ural. Book Publishing House, 1990. — p. 152.

- «International Herald Tribune», May 21, 1986.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 337–338.

- Moscow wants to revive “Beryozka” stores // Vesti.ru (www.vesti.ru). February 10, 2015, 15:54. [Online resource]. URL: https://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=2343683 (accessed: 29.11.2019).

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 348–349.

- Resolution of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) on Primary and Secondary Schools. Appendix No. 5 to item 31 of Politburo protocol No. 58 of August 25, 1931 // RGASPI. F. 17. Op. 3. D. 844. L. 22–29.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 339–340.

- A.A. Bek. «Novoe naznachenie: Roman». – 191 p. – Kishinev: “CONCORDIA-A. T.”, 1990. – p. 134.

- B.N. Yeltsin. «Confession on a Given Theme». – 240 p. – Sverdlovsk: Middle Urals Book Publishers, 1990. – p. 147.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class» (second edition, revised and expanded), 671 p. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — pp. 345–346.

- Ibid., p. 351.

- Ibid., pp. 346-347.

- “Rabochaya tribuna”, February 17, 1990

- “Süddeutsche Zeitung”, March 20, 1990

- M. Voslensky. Nomenklatura: The Ruling Class of the Soviet Union (Second revised and expanded edition), 671 pp. – Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. – pp. 369-370.

- Ibid., p. 142.

- Ibid., p. 144.

- Ibid., pp. 351-352.

- Ibid., p. 355.

- Ibid., pp. 353-354.

- Ibid., p. 256.

- GARF. F. R-8131. Op. 37. D. 4668. L. 126

- O. Khlevnyuk. Stalin: The Life of a Leader – Biography. – 464 pp. – Moscow: AST-CORPUS, 2015. – p. 431.

- Ibid., p. 338.

- Pavel Sudoplatov. Intelligence and the Kremlin. Notes of an Undesirable Witness. – 508 pp. – Moscow: TOO “Geya”, 1996. – p. 371.

- Gennady Krasukhin – A Year with Literature. Quarter Three

- Lev Parfenov – Cinema of Russia: Actor’s Encyclopedia, Vol. 2. – Materyk, 2008 – 225 pp.

- Interrogation protocol of the arrested L.P. Beria, July 14, 1953 // Politburo and the Beria Case. Document Collection / Ed. by O. B. Mozokhin. – 1088 pp. – Moscow: Kuchkovo Pole, 2012. – p. 98.

- Li Zhisui. «The Private Life of Chairman Mao». 2 vols. Vol. 1 / Translated from English by A.G. Skomorokhov. — 384 pp. – Minsk: Inter-Digest; Smolensk: TOO “Echo”, 1996. — pp. 124-125.

- M. Voslensky. «Nomenklatura: The Ruling Class of the Soviet Union» (Second, revised and expanded edition), 671 pp. — Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd London, 1990. — p. 323.